Episode 178

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- How dyscalculia changed Michele’s path in jewelry for the better

- Why Michele lets her hands guide her artistic process, and how she embraced her style of working

- Why jewelry artists don’t need to make their work smaller or more palatable to find a customer base

- How the Little Rock, Arkansas art scene compares to the rest of the country

- How Michele uses her jewelry to connect with patients

About Michele Cottler-Fox

Michele Cottler-Fox is a physician jeweler, with a studio practice focusing on translating fiber techniques to metal, primarily crochet, knitting, and twining, and often incorporating found objects to tell a story. She was one of four metal artists chosen for the Heavy Metal exhibit by the Arkansas committee for the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Additional Resources:

Photos:

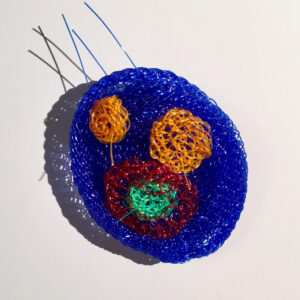

Fishing wire broaches

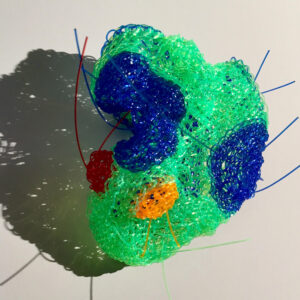

From the “Social distancing is awkward” series: Crochet mild steel and stone bead necklace

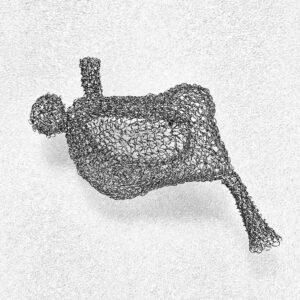

Steel brooch from the broken people series

“Life persists in the Cracks” series: Crochet Argentium brooch with tourmaline beads

Gold filled 28 g wire, Argentium wire, white freshwater pearls

Transcript:

Physician-jeweler Michele Cottler-Fox struggled with dyscalculia—a math learning disability—as a child. When she began to study jewelry, she found math-heavy jewelry fabrication methods and measurements nearly impossible to understand. But instead of stopping her jewelry career in its tracks, this disadvantage pushed Michele to make her freeform crocheted metal designs. She joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about how she embraced her creative process; where her career as a physician and her career as a jewelry artist intersect; and why she loves crocheted designs.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is the first part of a two-part episode. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it’s released later this week.

I am pleased to welcome Michele Fox to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. I’ve gotten to know Michele through several of the trips we’ve taken as part of Art Jewelry Forum. In addition to making very unusual jewelry, Michele is a physician who now works part time at the University of Arkansas Medical Center. We’ll learn all about her jewelry journey today. Michele, welcome to the program.

Michele: Thank you for having me, Sharon.

Sharon: I’m so glad. It’s great to have a chance to talk to you uninterrupted. Tell us about your jewelry journey. Were you artistic as a child? Did you know you wanted to be a doctor?

Michele: I come from a family where women didn’t sit with idle hands. My grandmother taught me to crochet and knit before I was six years old. I can remember very clearly her saying to me, “Don’t ever crochet. You do not know how to count properly.” I put the crochet hook away at an early age, picked up the needles and never looked back. I taught myself to embroider and to do needlepoint, but my family, for the most part, never thought about me as being a creative type. I did have a great aunt, very much an Auntie Mame type of person, who was a dress designer. She thought I was creative and tried very hard to encourage me, but the rest of the family, being engineers and physicians, they won.

Sharon: So, your family was more science oriented.

Michele: Very much.

Sharon: Can you tell us about your jewelry education? Did you go to GIA? What did your jewelry education entail?

Michele: I was self-taught from the beginning almost to the end. I grew up in a family where jewelry was the gift of preference for all special events. My father had worked as a teenager in an import/export business, so he knew many of the people involved in stone cutting and stone selling in New York City. I would tag along with him as a kid when he went to say hi. One of my favorite experiences was meeting a man who sold opals and being allowed to choose my own gift from everything in the case. It was overwhelming. While being seven or eight years old, there was a little glass bubble filled with opal chips and liquid that hung from a pendant. I still have it.

Sharon: Wow! And you still have it. Do you wear it? I haven’t seen it, I don’t think.

Michele: I pretty much stopped wearing anything around my neck when I began working in the hospital full time. Necklaces have a tendency to go straight down into patient’s faces which when you are trying to listen to their lungs or their heart.

Sharon: Were you attracted to glittery things besides this case?

Michele: I loved stones. I loved the color and the shape and the light when you move them. In fact, after graduate school, I took a class learning to cut stones and to polish them. I ran up against the fact that I’m both dyslexic and dyscalculic, which means measuring and numbers are very difficult for me. Although I could polish stones beautifully and evenly, I could never figure out the faceting machine. So, I gave that up.

Sharon: Did you want to be a maker after school?

Michele: I thought for many years that I wanted to be a maker of some sort, but there was really no time to go to school. So, I started designing jewelry and trying to find people to make it for me. There were a lot of gold and silversmiths in the Baltimore/ Washington area. I would look at what was available at the ACC Baltimore Craft Show and try to find a maker from my area who was showing there and talk them into making something for me. I rather rapidly learned that describing what you want to someone when you don’t understand what’s involved leads to some major disasters.

Sharon: That’s a really interesting idea. I never thought of that. It seems like on this side of the country, there’s not much going on.

I met you through Art Jewelry Forum, so I’ve only seen you be attracted to what I would call avant garde jewelry. What attracted you to that?

Michele: It was a very slow shift from classic jewelry onwards. I had exposure to good design from makers sold by Tiffany and Georg Jensen as a child and teenager. I didn’t know at the time that I was seeing Georg’s work and very famous Scandinavian gold and silversmiths. My husband and I lived in Sweden after I had a degree in research biology and before I went to medical school, and I discovered that all the things I liked best were Scandinavian. So, I started learning about classic Scandinavian jewelry while we lived there.

When I came back to the States after medical school, I started looking for galleries and more modern makers in the Baltimore/Washington area. I was very fortunate in meeting a gallerist who had a gallery at the time in Baltimore called Oxoxo, which no longer exists. The gallerist retired many years ago, but I would stop in on my way home after a Saturday on call at the hospital and she’d let me play. I would try everything on in the gallery. I would always find the one thing that wasn’t properly made. I’d say, “How does this work?” and then it would break in my hands, to the point where I felt I was a disaster. But the gallerist had a different take on it. She said, “You need to come the night before I open a show and try everything because then I’ll find the one thing that isn’t going to work. I wouldn’t have it in the show to scare people.” We got to be good friends, and she helped educate me about what I was looking at and the makers. One day she said, “You have such good ideas about what you’re looking at. You really need to learn how to make something like this,” but there was no time. The Maryland Institute College of Art, MICA, was literally visible from my office window in the hospital, but there was no time to go, which was very frustrating.

Then I was offered a job in Little Rock and took it. I suddenly discovered I had three hours a day in my life that I never had before because I was no longer commuting. There was a night school attached to the art center, and I started to take classes. Again, I came head-to-head with the fact that I’m dyscalculic, which means I can’t measure worth a darn and I can’t count, so fabrication drove me crazy. I couldn’t stand it. So, I stopped taking classes and I thought, “All right, I’m just going to figure this out on my own.”

I was home sick one weekend. I had a spool of wire I had bought for something that didn’t work, and I had crochet hooks and knitting needles at the side of the bed because that’s what I did when I was home alone. I thought, “I wonder,” and I picked up the spool of wire, which was silver. I threaded on some random beads and started to crochet, and the necklace self-assembled. I had no idea what I was doing, but my hands made something that was beautiful and wearable, and I thought, “O.K., I’ve got to do more of this.” I still have that necklace, which is amethyst beads on silver wire.

Sharon: You thought it was so beautiful. Did you consider selling it? What happened?

Michele: Absolutely. Selling started as an accident, as most good things in my life have been. I walked into a local gallery, and the gal behind the counter—who was the owner, it turned it out—looked at what I was wearing, my own work, and said, “Do you sell your work?” I said, “Well, I’d like to. Why?” She said, “I want to carry it.” So, I gave her some earrings and a couple of necklaces. Being very young at the business, I said to her, “Here’s my beeper number. I’m a physician. I’m always on call. If somebody actually buys one of these, please let me know.” She laughed, and I’ll be darned if two days later I didn’t get a beep saying, “Your earrings sold.”

Sharon: Did you make more?

Michele: Of course. I was hooked. It was a novel experience, that I could suddenly make somebody happy. I’m trained as a hematologist/oncologist, and most of what I have to tell patients does not make them happy.

Sharon: I can believe that.

Michele: This sense of joy that people got from picking up and trying my stuff on was an overwhelmingly positive experience that I wanted to continue.

Sharon: Did you consider yourself a salesperson?

Michele: No. I’m bad at it. The gallerist is now one of my best friends. She grew up in a retail family, and she shakes her head every time we do a show together. She knows how to present her work. She knows how to sell her work. I just tell people what I made, why I made it and how I did it. It’s good enough. They take my stuff home anyway.

Sharon: So, you don’t have to sell it; it sells itself.

Michele: It’s a very tactile form of jewelry, and it is very different from what most people are accustomed to seeing. I learned that there are some people who look at it and say, “Well, it looks like a Brillo pad. Why would I pay money for that?” and that’s O.K. I have no ego about it, none. I want my pieces to go to someone who loves it. I prefer that people who are not enthusiastic about it not have it.

Sharon: I have to stop here and say even though we show images on the website, we’re not showing what you’re talking about. Everything you have is crocheted or knitted wire. It’s all, like you said, the Brillo pad look. I never thought of a Brillo pad, but it’s wire crochet. It’s very interesting and freeform, much of it. What do you do?

Michele: My hands figure out what to make. For many years I thought that meant I wasn’t really an artist, until I started reading what artists I admired said about their own manner of working. I read an essay by Becky Kessler, who is a Dutch artist I love, and she said exactly the same thing I’ve been saying. Her hands decide what to make and she just goes along with it. As her hands work, she has many different options, but the choice of what to make is her hands’ choice.

Sharon: Do you have wire next to your chair or your bed and you just decide to do it?

Michele: That’s exactly right. The spools of wire are in a basket at bedside. The crochet hooks are in a copper bowl at bedside.

Sharon: Are you knitting or crocheting? I know the difference, but looking at it, I can’t tell.

Michele: Most of the time these days, I’m crocheting. Knitting is a little bit more difficult physically for me. I have to do it around the needle or it falls off continuously. The stitches don’t slip off the way they would if they were yarn, so it’s easy to recover, but it was more frustrating, I think. With the crocheted pieces, my hand can make round things or flat things. I noticed a long time ago that the hook is in my right hand, but my left hand actually forms what I’m making as I move. So, even when I teach someone to make exactly what I make, it never looks the same because their hand forms it differently.

Sharon: That’s interesting. Michele, there are two things I remember about you. One is that you didn’t speak any Swedish before you went to Sweden to medical school there, right?

Michele: That’s absolutely correct.

Sharon: That is amazing to me. And now you say you don’t know numbers or fractions. What you did is really amazing.

Michele: There are workarounds for everything if you’re determined. I think “determined” ought to have been my first name rather than Michele.

Sharon: Were you determined to be a doctor, a physician, a scientist, a bio-researcher? What were you going to be?

Michele: At the age of 12, having read science fiction hidden in my physician uncle’s library, I decided I wanted to go to space, but I knew even back then that, as a woman, I was going to have difficulty getting into an official program for space. I decided that if I were a physician and I had gone through a psychology major in college, I might have a better shot at it. I was thinking, “Be a surgeon. Have a backup plan as psychologist, and maybe there will be a position for me on a space station or a colony on the moon.”

Sharon: Where you can crochet.

Michele: I wasn’t even thinking about that. My grandmother had said, “Put it away. You don’t know how to count.” Once I decided that’s what I was going to do, I just walked in a straight line. I applied to colleges that had strong psychology programs. I ended up going to Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, which was the only school that Sigmund Freud had visited. It was also a college where Robert Goddard, the father of rocketry in this country, had worked. I had exactly what I wanted all in one place. Of course, taking the introduction to psychology class disabused me completely of the notion of being a psychologist. I ended up a biology major with a minor in English.

Sharon: That’s an interesting combination. I bet you’re the only one who has a biology major and a minor in English. What would your grandmother say now that you crochet and that people want the things you make?

Michele: I think about that often. I see her shaking her head or rolling her eyes. The English major put me in very good stead because I’ve been a language editor for all my working life. I primarily help people who do not have English as a first language but need to write in English.

Sharon: Do you read what they’ve written and say, “This is what you really meant to say,” or “This is how you’d say it in English”?

Michele: I fix it for them.

Sharon: I know you still work part time, but when you decided to retire, was your plan that you would have more time to make jewelry?

Michele: That was exactly what I had planned. I thought it would be a very easy segue from full-time physician to full-time artist. My initial plan was that I’d take the first year after retirement and go to school to learn better techniques. Of course, I chose to retire in July 2019, which meant I found myself confronting the pandemic.

Sharon: So, you had a lot of time on your own.

Michele: I had two straight years at home. I focused on making things that were much bigger than I had the time to make beforehand. As I was thinking about all the changes the pandemic was inflicting on us, I started to work in series. My first series I called “Social Distancing is Awkward.” As the pandemic progressed, I made a series called “Controlled, Constrained and Confined.”

Sharon: Was that just the name you gave it, or did you form it around the name?

Michele: In that case, I actually had the name first and I was thinking about how I could represent it. My hands gave me a way. I’ve always worked in series to some extent because as I make one thing, I see a different way I could have done it, and I need to make that in order to see if it works. After “Controlled, Constrained and Confined,” I made one called “What Galaxy Do You Live In?”

Sharon: When you said you made them larger, did you mean you wanted to bring them to a gallery? Were they too large to wear?

Michele: Very few of my things are too large to wear, particularly since I have a good friend and fellow member of AJF in Little Rock who says it’s not big enough. I have a couple of galleries in Little Rock that take my work. They’ve never shied away from any of the things I bring them, and I have brought several big things. People aren’t nearly as frightened of them as I always thought they would be, which has been a pleasant surprise. This year I’ve been working on a series called “Broken People” because of what I see around me.

Sharon: That’s a good name. I have to say I was very impressed with how creative Little Rock was. I never thought I’d ever be in Little Rock, but it was a very creative town.

We will have photos posted on the website. Please head to TheJewelryJourney.com to check them out.