Episode 175

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- Why sacred geometry is the underlying link between Eva’s work in jewelry, architecture and design

- How growing up in an isolated Soviet Bloc country influenced Eva’s creative expression

- Why jewelry is one of the most communicative art forms

- How Eva evaluates jewelry as a frequent jewelry show judge

- Why good design should help people discover new ideas and apply them in other places

About Eva Eisler

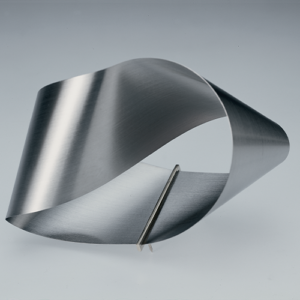

A star of the Prague art world, Eva Eisler is an internationally recognized sculptor, furniture/product designer, and jeweler. Rooted in constructivist theory, her structurally-based objects project a unique spirituality by nature of their investment with “sacred geometry.” The current series of necklaces and brooches, fabricated from stainless steel, are exemplars of this aesthetic. In 2003, she developed a line of sleek, stainless steel tabletop objects for mono cimetric design in Germany.

Eisler is also a respected curator and educator. She is chairman of the Metal and Jewelry Department at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, where she heads the award-winning K.O.V. (concept-object-meaning) studio. Her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum and Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in Canada; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; and Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, among others.

Additional Resources:

Photos:

Sculpture, Mobius Series 2:

Transcript:

Eva Eisler is the rare designer who works on projects as small as a ring and as large as a building. What connects her impressive portfolio of work? An interest in sacred geometry and a desire to discover new ideas that can be applied in multiple ways. She joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about how she communicates a message through jewelry; why jewelry students should avoid learning traditional techniques too early; and her thoughts on good design. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is the first part of a two-part episode. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it’s released later this week.

My guest today is Eva Eisler, s. She’s probably one of the most well-known artists in the Czech Republic. Her work is minimal and refined. She also designs clothing, furniture, sculpture and so many other things I can’t tell you about. She has taught and studied at Parsons School of Design, and she’ll fill us in on everything she’s learned. I’m sure I’m leaving something out, but she’ll fill us in today. Eva, welcome to the program.

Eva: Thank you for having me.

Sharon: Great to have you. Tell us about your jewelry journey. Did you study it? Were you artistic as a youth?

Eva: I only thought about this yesterday. You’re the first person I’m going to tell this story to. During the war, my grandfather, because he was very practical and forward-thinking, was buying jewelry from people who needed money to have safety deposits for later, whatever happened after the war. When I was born in 1952, there was still a little bit left of the treasure he collected and enclosed in a beautiful wooden treasure box. When I was a good girl, I could play with real jewelry in gold and stones.

When I grew older, I never thought of jewelry as something I would design. It was something I could play with as a girl, but when I got older, living in a communist country—Czechoslovakia turned into a Soviet Bloc country after the war—everything was so gray and constrained and monotonous. People were afraid to say whatever they thought, and I was feeling that I had to start something provocative, to start some kind of dialogue about different things. So, I started making jewelry, but because I didn’t know any techniques, I did it in the form of ready-mades, looking for different metal parts out of machines, kitchen utensils, a stainless-steel shower hose, a clock spring, sunglasses, all different things. I didn’t know people like that existed somewhere else, like Anni Albers, who in the 40s created a beautiful necklace out of paperclips. I learned that much, much later.

I was not only making jewelry. I was also making lamps and small sculptures, because creating things always made me happy. My mother was an art teacher. My father was a scientist. He was one of the founders of robotics in the 50s, and he ended up teaching at the most famous universities around the world later on. That’s how I started making jewelry, but I wanted to proceed with a profession in architecture. That was always my main interest. After school, I worked for a few years as an architect. Later on, I got married and had children, and I wanted to be free from a steady job and do what I loved most, create.

Sharon: When you were an architect, were you designing buildings?

Eva: I was part of a team for experience. I was given smaller tasks that I had to do, mostly parts of the interior.

Sharon: Did you do sculpture and jewelry on the side? Your sculpture is such a big part.

Eva: Yeah, we’re talking about when I was 25, 26. In 1983, my husband and I and our two children moved to New York, because John was invited by Richard Maier to come and work for him. That was a big challenge that one should not refuse. So, we did the journey, even though it was not easy with two little children.

Sharon: Did you speak English at all, or did you have to learn when you came?

Eva: I did because my father, in the 60s, when it was possible, was on a contract with Manchester University in England teaching. Me and my brothers went there for summer vacations for two years. One year, I was sent to one of his colleagues to spend the summer, and then I married John, who is half-British. His British mother didn’t speak Czech, so I had to learn somehow. But it was in Europe when I got really active, because I needed to express my ideas.

Sharon: Does your jewelry reflect Czechoslovakia, the Czech Republic? It’s different than jewelry here, I think.

Eva: There were quite a few people who were working in the field of contemporary avant garde jewelry. I can name a few: Anton Setka, Wasoof Siegler. Those were brilliant artists whose work is part of major museums around the world, but I was not focused on this type of work when I still lived in the Czech Republic, Czechoslovakia at that time. It was when I arrived in New York. I thought, “What am I going to do? I have two little children. Should I go and look for a job in some architecture office?” It would be almost impossible if you don’t have the means to hire babysitters and all the services. So, I thought, “I have experience with jewelry. I love it, and I always made it as a means of self-expression and a tool for communication. O.K., I am going to try to make jewelry, but from scratch, not as a ready-made piece out of components that I would find somewhere.”

I didn’t know any techniques. Somebody gave me old tools after her late husband died. I started trying something, and I thought, “Maybe I can take a class.” I opened the Yellow Pages looking at schools, and I closed my eyes and pointed my finger at one of the schools and called there. This woman answered the phone, and she said, “Why don’t you come and see me and show me what you did?” When I showed it to her, she said, “Are you kidding? You should be teaching here.” It was one of my ready-made pieces. Actually, a few years before I came to New York, I went to London and showed it to Barbara Cartlidge, who had the first gallery for contemporary jewelry anywhere in the world in London. She loved it. She loved my work, and she bought five pieces. She took my work seriously, because basically I was playing and wearing it myself and giving it to a few friends who would get it as a present. So, I was shocked and very pleased.

This is what I showed this woman at the Parsons School of Design. This woman was the chair that took care of the department. I said, “I cannot teach here. I don’t know anything,” and she said, “Well, clearly you do, but you’re right. You should take a class and get to know how the school works, and maybe we can talk about you teaching here a year later.” I took a foundation course in jewelry making. It was Deborah Quado(?) who taught it. One day she said to my classmates, “This woman is dangerous.” I forgot to say that before I started this class, the chair invited me to a party at her house to introduce me to her colleagues. It was funny, because I was fresh out of the Czech Republic, this isolated, closed country, and I was in New York going to a party. I needed those people that became my friends for life.

That was a super important beginning of my journey in New York into the world of jewelry. A few years later, when I made my first collection, someone suggested I show it to Helen Drutt. I had no idea who Helen Drutt was. She was somewhere in Philadelphia. I went there by train, and Helen is looking at the work and says, “Would you mind if I represent your work in the gallery?” I said, “Well, sure, that’s great,” but I had no idea that this was the beginning of something, like a water drain that pulls me in. The jewelry world pulled me in, and I was hooked.

From then on, I continued working and evolving my work. When I started teaching at Parsons, students would ask me whether they could learn how to solder and I said, “I advise you not to learn any traditional techniques because when you do, you will start making the same work as everybody else. You should give it your own way of putting things together.” At the end, I did teach them how to solder, and I was right.

I tried to continue with the same techniques I started when I was making these ready-made pieces, but with elements I created myself. Then I tried to put it together held by tension and different springs and flexible circles. I got inspired by bridges, by scaffolding on buildings, by electric power towers. I was transforming it into jewelry, and it got immediate attention from the press and from different galleries and collectors. I was onto something that kept me in the field, but eventually, when my kids grew older, this medium was too small for me. I wanted to get larger. Eventually, I did get back into designing interiors, but it was not under my own name.

Sharon: When you look at your résumé, it’s hard to distill it down. You did everything, sculpture, architecture, interior design and jewelry. It’s very hard to distill down. Interior design, does it reflect the avant garde aspect?

Eva: Yes, I am trying to do it my way. I love to use plywood and exposed edges to make it look very rough, but precise in terms of the forms. If you think of Donald Judd, for example, and his sculptures and nice furniture, it’s a similar direction, but I’m trying to go further than that. I’m putting together pieces of furniture and vitrines for exhibitions and exhibition designs. While I am taking advantage of the—

Sharon: Opportunity?

Eva: Opportunity, yes. Sorry. I don’t have that many opportunities lately to speak English, so my English is—

Sharon: It’s very good.

Eva: On the other hand, yes, I’m interested in doing all these things, especially things that I never did before. I always learn something, but it’s confusing to the outside world. “So, what is she? What is she trying to say?” For example, this famous architectural historian and critic, Kenneth Frampton from Columbia University, once said, “If one day somebody will look at your architectural works all together, they will understand that it’s tight with a link, an underlying link.”

Sharon: Do you think you have an underlying link? Is it the avant garde aspect? What’s your underlying link?

Eva: It’s the systems. It’s the materials. It’s the way it’s constructed. I’m a humble worshipper of sacred geometry. I like numbers that have played an important role in the past.

Sharon: Do you think the jewelry you saw when you came to the States was different than what you had seen before? Was it run-of-the-mill?

Eva: When I came to New York a few years later, I formed a group because I needed to have a connection. I organized a traveling show for this group throughout Europe and the group was—

Sharon: In case people don’t know the names, they are very well-known avant garde people.

Eva: All these people were from New York, and we exhibited together at Forum Gallery and Robert Lee Morris on West Broadway. That brought us together a few times in one show, and through the tours I organized in New York, Ghent, Frankfurt, Berlin, Vienna and Prague.

Sharon: Wow! We will have photos posted on the website. Please head to TheJewelryJourney.com to check them out.