Episode 174

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- How synesthesia—the ability to hear colors and see music—has impacted William’s work

- Inside William’s creative process, and why he never uses sketches or finishes a piece in one sitting

- Why jewelry artists should never scrap a piece, even if they don’t like it in the moment

- The benefits of being a self-taught artist, and why art teachers should never aim to impart their style onto their students

- How a wearer’s body becomes like a gallery wall for jewelry

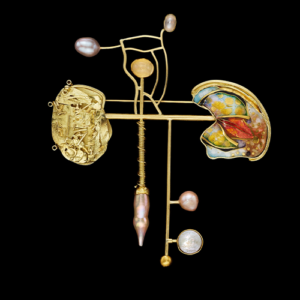

About William Harper

Born in Ohio and currently working in New York City, William Harper is considered one of the most significant jewelers of the 20th century. After studying advanced enameling techniques at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Harper began his career as an abstract painter but transitioned to enameling and studio craft jewelry in the 1960s. He is known for creating esoteric works rooted in mythology and art history, often using unexpected objects such as bone, nails, and plastic beads in addition to traditional enamel, pearls, and precious metals and stones.

His work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum Craft+ Design, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Philadelphia, the Hermitage Museum, totaling over 35 museums worldwide. A retrospective of his work, William Harper: The Beautiful & the Grotesque, was exhibited at the Cleveland Institute of Art in 2019.

Additional Resources:

William’s Instagram

Photos:

Transcript:

Rather than stifle his creativity, the constraints of quarantine lockdown and physical health issues helped artist-jeweler William Harper create a series of intricate jewels and paintings imbued with meaning. After 50+ years as an enamellist, educator and artist in a variety of media, he continues to find new ways to capture and share his ideas. He joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about his creative process; why he didn’t want his art students to copy his style; and why he never throws a piece in progress away, even if he doesn’t like it. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is the first part of a two-part episode. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it’s released later this week.

I’d like to welcome back one of today’s foremost jewelers, William Harper. To say he is a jeweler leaves out many parts of him. He’s a sculptor, an educator, an artist, an enamellist, and I’m sure I’ve leaving out a lot more. His work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Crafts, the Museum of Fine Arts, and most recently he had a one-person show, “The Beautiful & the Grotesque,” at the Cleveland Institute of Art. I can’t do justice to all of his work, so I’ll let him try to do some. Bill, welcome to the program.

William: Thank you. It’s great to see you again.

Sharon: It’s so great to see you after everything we’ve gone through. Give us an overview of how you got into jewelry and enameling, your art, everything. How did you get into it?

William: One of the questions you gave me to ponder ahead of time was if I was interested in jewelry when I was a child. I was not even interested in jewelry when I was in college, except for taking one course to make the wedding rings for my now ex-wife, but that was it.

A few years later, I got a phone call from Florida State University asking me if I would like to interview for a job teaching jewelry and metals and enameling. I wrote back and said, “I don’t think I’m the person you want, because I don’t know very much about jewelry.” So, I said no. Two days later, they called me again, and I told them the same thing. Then two days later, they called me again and I said, “Let me think about this. You’re on the quarter system. Are you willing to pay me for one quarter, when I’m not there and I’m cramming on how to teach jewelry?” The head of the department said, “That sounds like a great idea. As long as you can come three weeks ahead of the students, we’ll be happy.”

I’m basically self-taught except for watching people at a few workshops. I think being self-taught is a very valuable tool because I was not chained to the style or techniques of any major professor, which happens so much, especially to students coming out with MFAs. For years, their work will look pretty much like what their instructor was doing. I didn’t have that. I was my own instructor, and I was able to play out, in my 55-year career, how to do what I saw vaguely in my mind.

I should say at this point, I had synesthesia—I could never say it correctly—which is the ability to hear music and see colors or see a painting and hear music. I’m blessed with that. I used to think it was a chain around my neck, but I appreciate the fact that I can do something that very few people can do.

Sharon: You mean you see a painting or you hear music and you think about how that translates into art or jewelry? I’ll call what you do jewelry.

William: Yeah. The strangest one is I can smell an odor, whether it’s bad or something overly sweet, like old lady rose perfume or cigars, and I have an instant reaction where I see—I don’t see things; I sense things in my mind. That’s the way it works.

Sharon: You’ve talked about the dichotomy in your work. Does that play into it?

William: Oh, absolutely. I’ve always been in opposites. Long before I was doing jewelry, I had a very successful enamel career. I would usually make two different objects in the same physical format, but one would deal with sensations that are opposite of the other, such as light and dark, good and evil, colorful and noncolorful. That informed that work. Now, after all the years doing jewelry exclusively, I try to build diametrically opposed ideas into the forms.

You mentioned the exhibition the Cleveland Institute of Art gave me a few years ago, “The Beautiful & the Grotesque.” The title of that show epitomized what I’m usually doing in my work. Sometimes it’s not always obvious to the viewer, but it serves as a jumping point for me. If I can plug the catalogue—

Sharon: Please do.

William: Cleveland did a beautiful catalogue. Everything that was in the show was there. If you’re interested in it, it’s $25 plus $9.95 shipping. It adds up to $34.95. To get it, you can contact me at my email address, which is ArtWilliamHarper@mac.com.

Sharon: ArtWilliamHarper@mac.com.

William: Yes.

Sharon: We’ll have a thumbnail of that on the website so you can click on it and order it.

William: Good, you’ve seen the catalogue. Can you vouch for how beautiful it is?

Sharon: It’s a beautiful catalogue. It has everything, the jewelry, the boxes, all of the art. When I say boxes, I’m thinking of the ones that are really art pieces. You said you think a lot of art is about thinking. What do you think about when you’re doing your art?

William: It often starts way before I actually begin making anything. That’s a hard question to answer. For instance, I’ve done several series based on other artists, all of whom were painters. I prefer painting to jewelry right now, I have to say. But in terms of these influences, I would look at the work, for instance the work of Jean Dubuffet. He has incredibly beautiful, messy patterns that run—

Sharon: Who?

William: Jean Dubuffet.

Sharon: Oh, Dubuffet, yes.

William: I have loved his work for many, many years, and I have known that he was the instigator of what is called the art brut movement, which is art that is made by people that not only are not highly educated in universities or art departments, but they might have some kind of physical disability or mental disability, where they express themselves in these absolutely gorgeous, out of this world ways, not like any professional artist would do. Dubuffet collected those and was instrumental in having a museum set up—I think it was in Switzerland; I should know that—of this work.

Talking about dichotomy, I wanted to catch that quality of not knowing what I was doing along with my sophisticated technique and taste. So, I did this series. I think there are 10 pieces. In order to do it, as I got into the third or fourth piece, I decided I wanted to write an essay about what the series meant to me being put into this catalogue. So, I gave it the name Dubu.

Sharon: How?

William: D-U-B-U. I came up with idea that a Dubu is a fantastical creature that can infect your mind and cause you to do absolutely glorious things. It was just something I made up in my mind.

I should also say that I don’t start a piece and finish it immediately. I don’t even know where I’m going when I start a piece. I simply go into the studio and start playing around with the gold. I know that sounds silly, that somebody can play around with something as precious as gold. But in doing so, there’s another dichotomy. I’m able to come up with forms that I would never be able to otherwise. At this point, I should mention I do absolutely no sketches, diagrams, or beginning things on paper to guide me. I simply allow the materials to guide me. I trust in them and my manipulation of them that they will start leading me to see what I want to be after.

Sometimes these are small enamel pieces. Sometimes they’re more complex with gold pieces. Sometimes they’re a consideration of how to use a stone or a pearl. As I’m making these things, I know I can’t use them necessarily in piece number one. So, my idea is, “O.K., go to my idea for piece number two and follow the same format of making things, simply because they amuse me.” I don’t take myself seriously while I’m doing these things. I think that’s part of why they’re successful. I should say one of the qualities that my work has been lauded for is being humorous without being funny, without being a caricature. I have found that is a rather rough road to travel, but I’m able to facilitate it somehow.

Anyway, I have these pieces I made, piece number one and piece number two. I still want to play around with making, let’s say, a different kind of cloisonné enamel that had been used in pieces one and two. At that point, after I have made things that could become three different pieces, I take what I like and finish piece number one. As often as not, I think of the title first, which I know is a rather strange way to go about it. But in thinking of a title, it helps me guide the quality of the personage I’m dealing with.

So, I finished piece number one. I don’t take anything away from it at that point. When I get to piece number two, I’d better start making things for piece number four. There’s this manipulation where all the pieces start moving around on my desk. When I start seeing there is a conclusion in making each one successfully, I know I can stop. Often in that process, I paint myself into a corner. I don’t know where I’m going, but actually that’s the best part in terms of the quality of the piece, because it gives me the opportunity to really think about what I’m after. After I’ve contemplated that, I’m able to get out of the corner, and I do piece number two and piece number three. This is a process I’ve used my entire career.

I’ve done a series dedicated to Jasper Johns which is very intellectual, because he’s a very intellectual artist. I did a series on Fabergé. I don’t really like Fabergé. I admire him, but I don’t like him particularly. In my series, each brooch had an egg-shaped enamel part as a part of the physicality of the piece. One of the things I don’t like about Fabergé is that his work was very dry. It’s beautiful, but it’s dry. It doesn’t have any kind of emotion attached to it at all. It was perfect for the Russian nobility because they were decadent. They were inbred. They proceeded far too long in this sociological process. So, I changed it by having in each piece a little zip that went from the outside peripheral into the center, which was like a sperm getting to the egg and fertilizing it. That’s how I dealt with that matter.

I’ve also done a series on Cy Twombly, who is my favorite painter. I know people wonder how I can be influenced by his work, which I admire for its messiness. I wish I could do it. People either get Twombly or they don’t. When I look at a group of Twombly pieces, I’ll have an idea of how to start meshing these into the same process I mentioned before, with the Dubus. I think I did the Twomblys 25 years ago and they still look fresh. That’s how my process works.

Sharon: How do you know if you’ve hit a wall? If you say, “This isn’t going to work. I’m going to put it in the junk pile”?

William: I don’t put things in junk piles. It’s too expensive and the enamel is too precious. I just put the elements aside. I know if I’m doing a series of 10 pieces, or if I decide I want it to be 12 pieces—it’s never more than 12 in a series—by the time I get to 10 or 12, I had better have come to a conclusion with all those pieces and not have left off too many elements. I just put those aside. I might use them again in four years, five years. My work is rather slow because I think a lot about it, and I don’t have drawings to follow. I don’t think of myself as a designer; I think of myself as an artist who makes jewelry. There’s a difference.

Sharon: Do you know before you start how many pieces will be in a collection? Do you say, “I’m going to make 10 pieces. They’re going to be in the collection, and I have no idea what it is”?

William: Yeah, I generally set a goal for myself. There are other pieces I do that I call knee play pieces. Knee plays come from music. Robert Wilson collaborated on a piece that is now an iconic gem called Einstein on the Beach. It was in five acts, which, if you think my work is unintelligible, this work was almost totally unintelligible. But it appealed to a certain kind of mind as being exquisite.

Between each act, without scenery or costumes or anything like that, there were groups of instrumentalists and vocalists who would improvise. With the knee play pieces, it’s not determined what the music and the vocalization is going to be. The vocalization is not consisting of words; it’s consisting of almost primal sounds that are put together with a cadence of Phillip Glass music. The reason they call it knee play is that they connect the acts. As soon as this group of pieces, the knee play music, is over from act one, they will usually suggest some kind of music or situation you’re going to see in act two. That’s sort of a meandering, intellectual approach, but I really like the idea. In my career, I haven’t just made series. I’ve often done isolated pieces, and I would do those in order to open up thought processes I could use to get to the next series. Does that make sense?

Sharon: Yes. Is that how you got to the collection you did during lockdown quarantine?