Episode 161

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- Why the best modernist pieces are fetching record prices at auction today

- How “Messengers of Modernism” helped legitimize modernist jewelry as an art form

- The difference between modern jewelry and modernist jewelry

- Who the most influential modernist jewelers were and where they drew their inspiration from

- Why modernist jewelry was a source of empowerment for women

About Toni Greenbaum

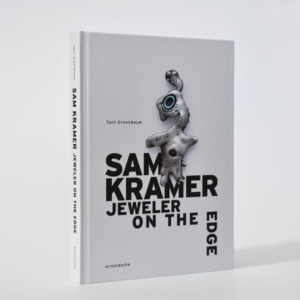

Toni Greenbaum is a New York-based art historian specializing in twentieth and twenty-first century jewelry and metalwork. She wrote Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960 (Montréal: Musée des Arts Décoratifs and Flammarion, 1996), Sam Kramer: Jeweler on the Edge (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2019) and “Jewelers in Wonderland,” an essay on Sam Kramer and Karl Fritsch for Jewelry Stories: Highlights from the Collection 1947-2019 (New York: Museum of Arts and Design and Arnoldsche, 2021), along with numerous book chapters, exhibition catalogues, and essays for arts publications. Greenbaum has lectured internationally at institutions such as the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum and Museum of Arts and Design, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art, Savannah. She has worked on exhibitions for several museums, including the Victoria and Albert in London, Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, and Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York.

Additional Resources:

Photos:

Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960 (photo: Giles Rivest; cover: Hahn Smith Design, Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts and Flammarion, Paris)

Sam Kramer: Jeweler on the Edge (photo: Chad Redmon; cover: Silke Nalbach, Arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart)

Transcript:

Once misunderstood as an illegitimate art form, modernist jewelry has come into its own, now fetching five and six-figure prices at auction. Modernist jewelry likely wouldn’t have come this far without the work of Toni Greenbaum, an art historian, professor and author of “Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry, 1940 to 1960.” She joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about the history of modernist jewelry; why it sets the women who wear it apart; and where collectors should start if they want to add modernist pieces to their collections. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is a two-part Jewelry Journey Podcast. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it comes out later this week.

Today my guest is art historian, professor and author Toni Greenbaum. She is the author of the iconic tome, “Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry, 1940 to 1960,” which analyzes the output of America’s modernist jewelers. Most recently, she authored “Sam Kramer: Jeweler on the Edge,” a biography of the jeweler Sam Kramer. Every time I say jeweler I think I’m using the world a little loosely, but we’re so glad to have you here today. Thank you so much.

Toni: I am so glad to be here, Sharon. Thank you so much for inviting me. It’s been many years coming.

Sharon: I’m glad we connected. Tell me about your jewelry journey. It sounds very interesting.

Toni: Well, there’s a lot you don’t know about my jewelry journey. My jewelry journey began when I was a preteen. I just became fascinated with Native American, particularly Navajo, jewelry that I would see in museum gift shops. I started to buy it when I was a teenager, what I could afford. In those days, I have to say museum gift shops were fabulous, particularly the Museum of Natural History gift shop, the Brooklyn Museum gift shop. They had a lot of ethnographic material of very high quality. So, I continued to buy Native American jewelry. My mother used to love handcrafted jewelry, and she would buy it in whatever craft shops or galleries she could find.

Then eventually in my 20s and 30s, I got outpriced. Native American jewelry was becoming very, very fashionable, particularly in the late 60s, 1970s. I started to see something that looked, to me, very much like Native American jewelry, but it was signed. It had names on it, and some of them sounded kind of Mexican—in fact, they were Mexican. So, I started to buy Mexican jewelry because I could afford it. Then that became very popular when names like William Spratling and Los Castillo and Hector Aguilar became known. I saw something that looked like Mexican jewelry and Navajo jewelry, but it wasn’t; it was made by Americans. In fact, it would come to be known as modernist jewelry. Then I got outpriced with that, but that’s the start of my jewelry journey.

Sharon: So, you liked jewelry from when you were a youth.

Toni: Oh, from when I was a child. I was one of these little three, four-year-olds that was all decked out. My mother loved jewelry. I was an only child, and I was, at that time, the only grandchild. My grandparents spoiled me, and my parents spoiled me, and I loved jewelry, so I got a lot of jewelry. That and Frankie Avalon records.

Sharon: Do you still collect modernist? You said you were getting outpriced. You write about it. Do you still collect it?

Toni: Not really. The best of the modernist jewelry is extraordinarily expensive, and unfortunately, I want the best. If I see something when my husband and I are antiquing or at a flea market or at a show that has style and that’s affordable, occasionally I’ll buy it, but I would not say that I can buy the kind of jewelry I want in the modernist category any longer. I did buy several pieces in the early 1980s from Fifty/50 Gallery, when they were first putting modernist jewelry on the map in the commercial aspect. I was writing about it; they were selling it. They were always and still are. Mark McDonald still is so generous with me as far as getting images and aiding my research immeasurably. Back then, the modernist jewelry was affordable, and luckily I did buy some major pieces for a tenth of what they would get today.

Sharon: Wow! When you say the best of modernist jewelry today, Calder was just astronomical. We’ll put that aside.

Toni: Even more astronomical: there’s a Harry Bertoia necklace that somebody called my attention to that is coming up at an auction at Christie’s. If they don’t put that in their jewelry auctions, they’ll put it in their design auctions. I think it’s coming up at the end of June; I forget the exact day. The estimate on the Harry Bertoia necklace is $200,000 to $300,000—and this is a Harry Bertoia necklace. I’m just chomping at the bit to find out what it, in fact, is going to bring, but that’s the estimate they put, at $200,000 to $300,000.

Sharon: That’s a lot of money. What holds your interest in modernist jewelry?

Toni: The incredible but very subtle design aspect of it. Actually, tomorrow I’m going to be giving a talk on Art Smith for GemEx. Because my background is art history, one of the things I always do when I talk about these objects is to show how they were inspired by the modern art movements. This is, I think, what sets modernist jewelry apart from other categories of modern and contemporary jewelry. There are many inspirations, but it is that they are very much inspired by Cubism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Biomorphism, etc., depending on the artist. Some are influenced by all of the above, and I think I saw that. I saw it implicitly before I began to analyze it in the jewelry.

This jewelry is extraordinarily well-conceived. A lot of the craftsmanship is not pristine, but I have never been one for pristine craftsmanship. I love rough surfaces, and I love the process to show in the jewelry. Much of the modernist jewelry is irreverent—I use the word irreverent instead of sloppy—as far as the process is concerned. It was that hands-on, very direct approach, in addition to this wonderful design sense, which, again, came from the modern art movements. Most of the jewelers—not all of them, but most of them—lived either in New York or in Northern or Southern California and had access to museums, and these people were aesthetes. They would go to museums. They would see Miro’s work; they would see Picasso’s work, and they would definitely infuse their designs with that sensibility.

Sharon: Do you think that jumped out at you, the fact that they were inspired by different art movements, because you studied art history? You teach it, or you did teach it at one time?

Toni: No, just history of jewelry. I majored in art history, but I’ve never taught art history. I’ve taught history of jewelry. We can argue about whether jewelry is art or not, but history of jewelry is what I’ve taught.

Sharon: I’ve taken basic art history, but I couldn’t tell you some of the movements you’re talking about. I can’t identify the different movements. Do you think it jumped out at you because you’re knowledgeable?

Toni: Yes, definitely, because I would look at Art Smith and I would say, “That’s Biomorphism.” I would see it. It was obvious. I would look at Sam Kramer and I would say, “This is Surrealism.” He was called a surrealist jeweler back in his day, when he was practicing and when he had his shop on 8th Street. I would look at Rebajes and I would see Cubism. Of course, it was because I was well-versed in those movements, because what I was always most interested in when I was studying art history were the more modern movements.

Sharon: Did you think you would segue to jewelry in general? Was that something on your radar?

Toni: That’s a very interesting question because when I was in college, I had a nucleus of professors who happened to have come from Cranbrook.

Sharon: I’m sorry, from where?

Toni: Cranbrook School of Art.

Sharon: O.K., Cranbrook.

Toni: I actually took a metalsmithing class as an elective, just to see what it was because I was so interested in jewelry, although I was studying what I call legitimate art history. I was so interested in jewelry that I wanted to see what the process was. I probably was the worst jeweler that ever tried to make jewelry, but I learned what it is to make. I will tell you something else, Sharon, it is what has given me such respect for the jewelers, because when you try to do it yourself and you see how challenging it is, you really respect the people who do it miraculously even more.

So, I took this class just to see what it was, and the teacher—I still remember his name. His name was Cunningham; I don’t remember his first name. He was from Cranbrook, and he sent the class to a retail store in New York on 53rd Street, right opposite MOMA, called America House.

Sharon: Called American House?

Toni: America House. America House was the retail enterprise of the American Craft Council. They had the museum, which was then called the Museum of Contemporary Crafts; now it’s called MAD, Museum of Arts and Design. They had the museum, and they had a magazine, Craft Horizons, which then became American Craft, and then they had this retail store. I went into America House—and this was the late 1960s—and I knew I had found my calling. I looked at this jewelry, which was really fine studio jewelry. It was done by Ronald Pearson; it was done by Jack Kripp. These were the people that America House carried. I couldn’t afford to buy it. I did buy some of the jewelry when they went out of business and had a big sale in the early 1970s. At that time I couldn’t, but I looked at the jewelry and the holloware, and I had never seen anything like it. Yes, I had seen Native American that I loved, and I had seen Mexican that I loved. I hadn’t yet seen modernist; that wasn’t going to come until the early 1980s. But here I saw this second generation of studio jewelers, and I said, “I don’t know what I’m going to do with this professionally, but I know I’ve got to do something with it because this is who I am. This is what I love.”

Back in the late 1960s, it was called applied arts. Anything that was not painting and sculpture was applied art. Ceramics was applied art; furniture was applied art; textiles, jewelry, any kind of metalwork was applied art. Nobody took it seriously as an academic discipline in America, here in this country. Then I went on to graduate school, still in art history. I was specializing in what was then contemporary art, particularly color field painting, but I just loved what was called the crafts, particularly the metalwork. I started to go to the library and research books on jewelry. I found books on jewelry, but they were all published in Europe, mostly England. There were things in other languages other than French, which I could read with a dictionary. There were books on jewelry history, but they were not written in America; everything was in Europe. So, I started to read voraciously about the history of jewelry, mostly the books that came out of the Victoria & Albert Museum. I read all about ancient jewelry and medieval jewelry and Renaissance jewelry. Graham Hughes, who was then the director of the V&A, had written a book, “Modern Jewelry,” and it had jewelry by artists, designed by Picasso and Max Ernst and Brach, including things that were handmade in England and all over Europe. I think even some of the early jewelers in our discipline were in that book. If I remember correctly, I think Friedrich Becker, for example, might have been in Graham Hughes’ “Modern Jewelry,” because that was published, I believe, in the late 1960s.

So, I saw there was a literature in studio jewelry; it just wasn’t in America. Then I found a book on William Spratling, this Mexican jeweler whose work I had collected. It was not a book about his jewelry; it was an autobiography about himself that obviously he had written, but it was so rich in talking about the metalsmithing community in Taxco, Mexico, which is where he, as an American, went to study the colonial architecture. He wound up staying and renovating the silver mines that had been dormant since the 18th century. It was such a great story, and I said, “There’s something here,” but no graduate advisor at that time, in the early 70s, was going to support you in wanting to do a thesis on applied art, no matter what the medium. But in the back of my mind, I always said, “I’m going to do something with this at some point.”

Honestly, Sharon, I never thought I would live to see the day that this discipline is as rich as it is, with so much literature, with our publishers publishing all of these fantastic jewelry books, and other publishers, like Flammarion in Paris, which published “Messengers of Modernism.” Then there’s the interest in Montreal at the Museum of Fine Arts, which is the museum that has the “Messengers of Modernism” collection. It has filtered into the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas, obviously MAD. So many museums are welcoming. I never thought I would live to see the day. It really is so heartening. I don’t have words to express how important this is, but I just started to do it. In the early 1970s or mid-1970s—I don’t think my daughter was born yet. My son was a toddler. I would sit in my free moments and write an article about William Spratling, because he was American. He went to Mexico, but he was American. He was the only American I knew of that I could write about. Not that that article was published at that time, but I was doing the research and I was writing it.

Sharon: That’s interesting. If there had been a discipline of jewelry history or something in the applied arts, if an advisor had said, “Yes, I’ll support you,” or “Why don’t you go ahead and get your doctorate or your master’s,” that’s something you would have done?

Toni: Totally, without even a thought, yes. Because when I was studying art history, I would look at Hans Holbein’s paintings of Henry VIII and Sir Thomas More, and all I would do was look at the jewelry they were wearing, the chains and the badges on their berets. I said, “Oh my god, that is so spectacular.” Then I learned that Holbein actually designed the jewelry, which a lot of people don’t know. I said, “There is something to this.” I would look at 18th century paintings with women, with their pearls and rings and bracelets, and all I would do was look at the jewelry. I would have in a heartbeat. If I could have had a graduate advisor, I would have definitely pursued that.

Sharon: When you say you never thought you’d live to see the day when modernist jewelry is so popular—not that it’s so surprising, but you are one of the leaders of the movement. When I mentioned to somebody, “Oh, I like modernist jewelry,” the first thing they said was, “Well, have you read ‘Messengers of Modernism?’” As soon as I came home—I was on a trip—I got it. So, you are one of the leaders.

Toni: Well, it is interesting. It is sort of the standard text, but people will say, “Well, why isn’t Claire Falkenstein in the book? She’s so important,” and I say, “It’s looked upon as a standard text, but the fact is it’s a catalogue to an exhibition. That was the collection.” Fifty/50 Gallery had a private collection. As I said before, they were at the forefront of promoting and selling modernist jewelry, but they did have a private collection. That collection went to Montreal in the 1990s because at that time, there wasn’t an American museum that was interested in taking that collection. That book is the catalogue of that finite collection. So, there are people who are major modernist jewelers—Claire Falkenstein is one that comes to mind—that are not in that collection, so they’re not in the book. There’s a lot more to be said and written about that movement.

Sharon: I’m sure you’ve been asked this a million times: What’s the difference between modern and modernist jewelry?

Toni: Modern is something that’s up to date at a point in time, but modernist jewelry is—this is a word we adopted. The word existed, but we adopted it to define the mid-20th century studio jewelry, the post-war jewelry. It really goes from 1940 to the 1960s. That’s it; that’s the time limit of modernist jewelry. Again, it’s a word we appropriated. We took that word and said, “We’re going to call this category modernist jewelry because we have to call it something, so that’s the term.” Modern means up to date. That’s just a general word.

Sharon: When you go to a show and see things that are in the modernist style, it’s not truly modernist if it was done today, it wasn’t done before 1960.

Toni: Right, no. Modernist jewelry is work that’s done in that particular timeframe and that also subscribes to what I was saying, this appropriation of motifs from the modern art movement. There was plenty of costume jewelry and fine jewelry being done post-war, and that is jewelry that is mid-20th century. You can call it mid-20th century modern, which confuses the issue even more, but it’s not modernist jewelry. Modernist jewelry is jewelry that was done in the studio by a silversmith and was inspired by the great movements in modern art and some other inspirations. Art Smith was extremely motivated by African motifs, but also by Calder and by Biomorphism. It’s not religious. There are certainly gray areas, but in general, that’s modernist jewelry.

Sharon: I feel envious when you talk about everything that was going in on New York. I have a passion, but there’s no place on the West Coast that I would go to look at some of this stuff.

Toni: I’ll tell you one of the ironies, Sharon. Post-war, definitely through the 1950s and early 1960s, there must have been 13 to 15 studio shops by modernist jewelers. You had Sam Kramer on 8th Street and Art Smith on 4th Street and Polo Bell, who was on 4th Street and then he was on 8th Street, and Bill Tendler, and you had Jules Brenner, and Henry Steig was Uptown. Ed Wiener was all over the place. There were so many jewelers in New York, and I never knew about them. I never went to any of their shops. I used to hang out in the Village when I was a young teenager, walked on 4th Street; never saw Art Smith’s shop. He was there from 1949 until 1977. I used to walk on 8th Street, and Sam Kramer was on the second floor. I never looked up, and I didn’t know this kind of jewelry existed. In those days, like I said, I was still collecting Navajo.