Episode 149

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- How David earned the nickname the “100-carat man” for selling some of the most expensive jewels in history

- What type of buyers are interested in eight-figure gems

- How David got the opportunity to write “Understanding Jewelry” with Daniela Mascetti

- Why the most incredible jewelry may be off the beaten path

- Why 18th century jewelry is so rare, and why people have refashioned old jewelry throughout history

About David Bennett

Regarded internationally as a leading authority in the field of precious stones and jewelry, David Bennett is best known in his role as Worldwide Chairman of Sotheby’s Jewelry Division, a post he held until 2020, after a brilliant 42 years career at Sotheby’s. During his prestigious career David sold three of the five most expensive jewels in auction history and as well as seven 100-carat diamonds – earning him the nickname the ‘100-carat man’.

David has also presided over many legendary, record-breaking auctions such as the Jewels of the Duchess of Windsor (1987), The Princely Collections of Thurn und Taxis (1992) and Royal Jewels from the Bourbon-Parma Family (2018).

Among the many records achieved during his career as an auctioneer is that for the highest price ever paid for a gemstone, the CTF Pink Star, a 59.60ct Vivid Pink diamond which sold for $71.2 million in 2017, and the world record for any jewelry sale where he achieved a total of $175.1 million in May 2016.

David was named among the top 10 most powerful people in the art world in December 2013 by the international magazine Art + Auction. In June 2014, Swiss financial and business magazine Bilan named him among the top 50 “most influential people in Switzerland”.

David Bennett is co-author, with Daniela Mascetti, of the best-selling reference book Understanding Jewelry, in print since 1989. They have also co-written Celebrating Jewelry, published in 2012. In 2021, David and Daniela launched a unique website showcasing their unparalleled experience and knowledge in the field of jewelry.

David Bennett grew up in London and graduated from university with a degree in Philosophy, a subject about which he is still passionate, alongside alchemy and hermetic astrology.

Additional Resources:

Website:

https://www.understanding-jewellery.com/

Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/understandingjewellery/

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/UnderstandingJewellery

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/UJewellery_

LinkedIn:

https://www.linkedin.com/company/19192787

Photos:

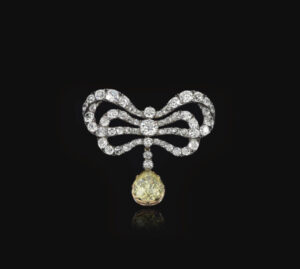

Lot 95:

From the Royal Jewels of the Bourbon Parma Family / 14th November 2018, Geneva

Diamond brooch, second half of the 18th century

Of double ribbon bow design set with cushion-shaped and circular-cut diamonds, second half of the 18th century, supporting a detachable pendant set with a pearl-shaped diamond of yellow tint, probably early 19th century

The double ribbon bow from Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France (1755-1793)

Sold for $2.1m

Lot 100:

From the Royal Jewels of the Bourbon Parma Family / 14th November 2018, Geneva

Exceptional and highly important natural pearl and diamond pendant, 18th century

Formerly in the collection of Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France (1755-1793)

The pearl and diamond bow motif were suspended from Marie-Antoinette’s three strand pearl necklace

Sold for $36.2m | The world record price for a pearl

Pink Star, sold April 2017, Hong Kong

Oval mixed-cut, internally flawless fancy vivid pink diamond weighing 59.60 carats, mounted in platinum

Sold for $71.2m | The world record price for any jewel at auction

Star of the Season, sold May 1995, Geneva

Pear-shaped, internally flawless D colour diamond weighing 101.10 carats

Sold for $16.5m | The world record price for a diamond at the time

Transcript:

Whether you know his name or not, David Bennett is responsible for some of the most significant jewelry auctions in history. Before retiring from Sotheby’s in 2020, David sold the Pink Star, the most expensive gem ever sold at auction, and whopping seven 100-carat diamonds. He’s also the co-author of the jewelry bible “Understanding Jewelry” with his colleague Daniela Mascetti. He joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about his new business with Daniela; what it was like to handle some of the world’s most precious jewels; and why he thinks gemstones hold incredible power. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is the second part of a two-part episode. Today, my guest is David Bennett, who you may be familiar with. He coauthored with Daniela Mascetti what is often referred to as the Bible of the jewelry industry, and that is the ubiquitous book, “Understanding Jewelry.” David spent his 40-year at the international auction house Sotheby’s. When he left, he held the position of Worldwide Chairman of International Jewelry. He’s a veteran of gemstones and is often called the “100-carat man” because of his multiple sales of hundred-carat diamonds at record-breaking prices. Welcome back.

So, you have hidden gems. Now, are the hidden treasures, the hidden gems, the ones you say, “We think this is a great piece of jewelry,” are those available for people to buy?

David: Yeah, not through us. Basically, we’re offering to be the eyes for collectors. Let’s say in London at a certain resale, we might find a great piece of 1925 Cartier. We’ll photograph it and write what we think about it. It’ll be an appraisal, as it were. This is what you wouldn’t see if you went down the main streets. I think in London the most important resales of collectible jewelry are of the 19th century, early 20th century jewelry. Our offices are not at street level, only shop fronts. We hope at least it’ll be used to appeal to collectors from the Far East who, if they arrive in London or Geneva or Paris, don’t quite know where to go.

Daniela is an excellent lecturer and a great jewelry historian, so she’s been doing these online courses. For example, one recently was on Art Deco. We’re going to be offering those. That’s the other rung, the other important part of Understanding Jewelry, the website we want to do. It’s an education thing as well, not because it’s just education, but also because I think the more you know about something, the more interesting it becomes. You could have some very beautiful jewelry, but the more you know about it, the more interesting it becomes. When you’re wearing it, you know more about it. Does that make sense?

Sharon: Yes, it makes a lot of sense. She is an excellent lecturer. I took the Art Deco class online, and I’m looking forward to more of your educational classes.

David: Absolutely, yeah.

Sharon: You mentioned that when you started out in the auction world, it wasn’t collectors or private individuals who came; it was people in the trade, and they’d break up the jewels and that sort of thing. Why did it change? How did it change? What happened?

David: This is back in 1974 with the first sales in London. It’s difficult to imagine now, but there was absolutely no market for 1930s jewelry. If you had big, 1930s diamond bracelets, believe it or not, they were sold and immediately broken up. The stems were taken out and reused, very often poor or bizarrely. The cushion-shaped diamonds in the set were then recut. It’s a modern brilliance. Everything changes. Nowadays people will pay premiums for the old stems and of course, as you know, 1930s jewelry is very, very sought after now.

Sharon: Yes, it’s very hard to find, the 30s. You can find some 40s and of course 50s, but not the 30s. So, what changed?

David: It changes all the time. It happens. This is not something new. In the 19th century, jewelry was being broken up and redesigned all the time. Up until about the 1840s, all the gold had to be reused because they weren’t finding gold—you had the California Gold Rush and then South Africa and everywhere else. In fact, it’s been estimated that something like 90 or 80 percent of the gold in use in 1800 had been in use since Roman times. The other thing is that jewelry is set with stones that are very hard, very durable. Gold doesn’t oxidize. It can be melted down very easily into this basal moss. So, all of this made it very susceptible to being remodeled and restyled.

In the 19th century, this was happening all the time. If you were a fashionable lady in the 1850s, you wouldn’t want to wear, if you could avoid it, an 1830s or 1820s brooch because it would be out of fashion. Everything was in check. This is, of course, very good news for the jewelers who were reusing things, but it made jewelry from before that period much rarer. 18th century jewelry is really, really rare. Diamond jewelry is as rare as hen’s teeth, but most of it, if you think about the great 18th century diamond jewelry, is in the Kremlin from the Catherine the Great period, even though they sold most of it. The Soviets sold it in the 1920s.

The point I’m trying to make is that refashioning and redesigning jewelry is nothing new. In the 20th century, the phenomenon I was watching was the grand jewelry. When you think about it, by the end of the decade—I’m talking about the 1970s—Art Deco jewelry was already becoming collected, so they weren’t breaking them up anymore; they were trying to keep them. But who knows how many bracelets and jewels from that period disappeared. That was from the 1930s to the 1980s, about 50 years.

What we’ve noticed is that the gap between when something is out of fashion and then becomes a classic and returns to fashion has become shorter and shorter. Nowadays people are talking about how desirable 80s jewelry is. It is shortening. So, I think there’s still a lot of room for new collectors to decide where they would like to position themselves. By the mid-90s, there was only one buying public; she was in the Middle East before the fortunes being made from the oil industry. It’s significantly changed the whole look of jewelry, and it started at the end of the 70s. In 1970, you’d walk around Place Vendome in Paris, the great address, and see the great French jewelry. Everything in the windows would have been in platinum and diamonds and so forth, but by the end of the decade, you wouldn’t really see platinum and diamonds; everything would be in yellow gold, which the Middle East likes. There would be colored stones. It would be very colorful. There was a mad scramble during the 70s and 80s to redesign everything for this new market, which had very clear ideas about what they wanted.

The one thing about jewelry, as I say, is that it can be designed relatively quickly, but the invention is the problem, coming up with these new designs, having a style. That’s why everybody looks back to the great years from the middle of the 19th century to 1960, when all these wonderful, new designs were changing. They were really groundbreaking designs.

Sharon: What were your thoughts when you started seeing private individuals at auctions as well as dealers? Did they start trickling in? How did it happen?

David: There were very few private individuals that came to the London jewelry sales in the 70s. They were collectors, so they would argue as to what was coming up. There were a few, a handful of them probably. I can’t think of exactly the date, but around this time, Sotheby’s had purchased a New York brand, Park Van Ness. Very few offices existed at that time. I think there were offices in Florence and Paris when I was there, but there wasn’t this massive expansion that happened in the 80s, which made Sotheby’s increase worldwide.

It was a massive change, and I had my sales like the Duchess of Windsor’s jewels, which was a career-defining moment for me. By then, you had people bidding by telephone from all over the world. It was completely different. The auction room was packed with private individuals clamoring to buy a piece of history, the jewelry where the King of England had given up his throne for the love of a woman. What an amazing story! It caught the imagination of every newspaper in the world. It was fantastic, and it was great jewelry.

The Duke of Windsor, before he was crowned—because he wasn’t crowned—and Wallis Simpson, the American socialite, they both absolutely adored jewelry and had very clear ideas of what they wanted, so the collection was just stunning. I remember when I was doing the catalogue, interviewing Jacques Arpels of Van Cleef & Arpels. He was recounting these extraordinary stories about how the Duke and Duchess would come into Van Cleef & Arpels, and he, as a young man, would have participated in the design of these jewels because they knew clearly what they wanted. If you look at some of the designs in the catalogue, they really are museum pieces. They transformed the look of jewelry in the 20th century, so it was wonderful stuff. That catalogue was a memorable moment.

Sharon: Wow! I can understand that. That would definitely be seared in your mind. I was reading one of the interviews with you in the New York Times. You talk about the fact that with your new business, you wanted to instill a sense of wonder in jewelry. Do you think that has been lost a little?

David: I guess what I was trying to say was that you get to an age—I’m coming to 70 soon, if I make it, very soon actually, alarmingly soon—and you start thinking, “I ought to try to give back some of the pleasure that I’ve got out of this totally unexpected path that I’ve trodden for the last 46 years, or however long it is.” One of the things that used to amaze me, and still does, is the power. The world-record ruby that I sold, I named it the Sunrise Ruby after this wonderful poem by Rumi, the 14th century poet. The owner showed it to me and it literally took my breath away. I was so shocked by it. First of all, it was 25 carats, a huge size for a Burma ruby, the top color. Everything about it was absolutely sensational, magnificent, towering, sterling. I wanted to try to communicate the effects that stone had on me and why, and what I think some people miss. The reason a lot of people miss it is because they haven’t been as fortunate as I have of seeing something like that. You wouldn’t see it walking down Madison Avenue. It wouldn’t be in a window.

Nevertheless, if you can imagine the most wonderful ruby you’ve ever seen, the most wonderful red, a stone like that has infinite power. I made a little video about the Sunrise Ruby. If you look at it online on the Understanding Jewelry site, I talk about why this is so important, particularly to me. It enters into this thing I have with astrology. Rubies, like all gemstones, are related to very important spiritual centers in the body. So, the effect, at least what I sensed, is really felt in the body. The ruby particularly, is known in India as the rise of the king of gemstones, more than diamonds, more than anything else, because it is so powerful. A lot of people say, “Yeah, a ruby’s powerful.” It sounds a bit new age, doesn’t it? But I promise you—like I said, I’m not telling a story; this is true—a ruby of that quality and that size and that color is unspeakable. It’s a wonderful thing. What I wanted to try to communicate is a sense of wonder, because when you’re looking at it, it’s like there’s nothing else; there is only that stone.

Sharon: Did working with gems lead to astrology, or was it philosophy and then to astrology? How did that work?

David: Actually, it’s very interesting. As an astrologer, I was constantly look at patterns, looking backward, looking at the past. Where was it coming from? Where is it leading? Why did it go off in that direction and then come back? Because everything in the end is linked. There’s nothing random about anybody’s life. Nothing happens to you, none of the people you meet, none of the people you marry, none of the places you go are by chance. There’s a reason why I know all of that—and actually, if you think about it, it’s pretty obvious—but what’s not obvious is what the reasons are and what the patterns are.

Let’s say I’d been halfway through 20 years into working with jewelry at auction and at the same time, I was doing more and more in astrology, more and more consulting. I don’t do astrology for money. I don’t charge; I refuse to charge, but I also refuse to do somebody’s chart if there’s anything with which I can help. That’s the playoff, but actually I don’t need to charge. If ever I need somebody to feed myself, then maybe I would. It’s as simple as that. I received it freely, and I’m very pleased to give it back freely. I began to say, “Look, I’ve spent 20 years in jewelry and gemstones out of the blue” when really, if you had asked me at the beginning what I was going do, I would have thought it would be something to do with astrology, making films about it, something like that.

Sharon: I think philosophy is such a brain twister just from my limited exposure to it. I just say, “I’m not good at puzzles.” I admire the fact that it was of such interest to you because for me, it was like, “Oh my god!”

David: Oh, really? I’ve got this property I’m setting out in Burgundy. It’s quite a large, rambling place, and it has a room I’m making into a lecture room. The last two years, of course, nothing has happened. So, I’ve organized with a group of friends some seminars on various subjects. The last one was about ayurveda.

Sharon: It was about what? I’m sorry.

David: Ayurveda.

Sharon: Oh, ayurveda, O.K.

David: And we invited David Frawley, who has written more than 50 books about ayurveda. He’s the great guru of ayurveda, and we built a seminar around him. That’s just one example, but I’ve been doing them maybe once or twice a year, and we’ve done many things. 20 years ago, the first one I gave was about sacred geometry, for example, but more recently they’ve been about healing plants, wild healing herbs and so forth. That’s been great fun. It’s nonprofit. It’s just for fun. Well, more than fun; hopefully people get more than fun out of it, but it’s a different type of learning. It’s trying to get people to look more inwards rather than outwards, if you know what I mean. It’s been a great success, and it’s a great success largely because people have made it a success. It’s a great pleasure for me to be able to share this place with other people to make it work.

Sharon: I’ll have to look at my jewelry again and think about what I was thinking at the time. Sometimes I do ask myself, “What was I thinking?” David, thank you so much for being with us today. It’s great to talk with you.

David: I was interested and it’s good fun. Thank you.

Sharon: Thank you so much.

Thank you again for listening. Please leave us a rating and review so we can help others start their own jewelry journey.