Episode 145

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- How Cindi helped the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston secure one of the country’s most important art jewelry collections

- Why jewelry is a hybrid of craft and art that doesn’t fit just in one category

- Why the art world began to question the value of craft in the 80s, and why that perspective is changing now

- Why museum and gallery visitors shouldn’t ask themselves, “Would I wear this?” when looking at art jewelry

About Cindi Strauss

Cindi Strauss is the Sara and Bill Morgan Curator of Decorative Arts, Craft, and Design and Assistant Director, Programming at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH). She received her BA with honors in art history from Hamilton College and her MA in the history of decorative arts from the Cooper-Hewitt/Parsons School of Design. At the MFAH, Cindi is responsible for the acquisition, research, publication, and exhibition of post-1900 decorative arts, design, and craft. Jewelry is a mainstay of Cindi’s curatorial practice. In addition to regularly curating permanent collection installations that include contemporary jewelry from the museum’s collection, she has organized several exhibitions that are either devoted solely to jewelry or include jewelry in them. These include: Beyond Ornament: Contemporary Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection (2003–2004); Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection (2007); Liquid Lines: Exploring the Language of Contemporary Metal (2011); and Beyond Craft: Decorative Arts from the Leatrice S. and Melvin B. Eagle Collection (2014). Cindi has authored or contributed to catalogs and journals on jewelry, craft, and design topics, and has been a frequent lecturer at museums nationwide. She also serves on the editorial advisory committee for Metalsmith magazine.

Additional Resources:

Photos:

View of inaugural exhibition of Decorative Arts, Craft and Design in the Cindi Strauss Gallery of the Kinder Building, January 22, 2021 Photo Copyright: Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Photographer: Will Michels

Exterior view of the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, August 31, 2021 Photo Copyright: Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Photographer: Will Michels

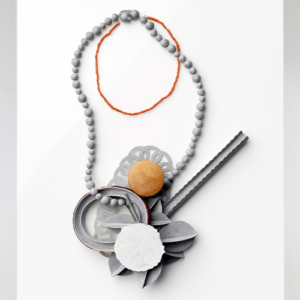

Artist: Lucy Sarneel, Dutch, 1961–2020 “Meli-melo” Necklace Date: 2007 Zinc, textile, rubber, wood, paint, glass beads, and gold

12 1/4 × 8 1/2 × 1 5/8 in. (31.1 × 21.6 × 4.1 cm)

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Gift of the Rotasa Collection Trust, 2015.86 © Lucy Sarneel Photo Copyright: Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Photographer: Thomas R. DuBrock Additional Copyright Holder (if known):

Lucy Sarneel

Artist: Joyce J. Scott, American, born 1948 “The Sneak” Necklace Date: 1989 Beads and thread Overall: 13 1/2 × 11 × 2 1/4 in. (34.3 × 27.9 × 5.7 cm) The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Helen Williams Drutt Collection, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Foundation, 2002.4077 © Joyce J. Scott Photo Copyright: Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Photographer: Thomas R. DuBrock Additional Copyright Holder (if known):

Joyce J. Scott

Artist: Claus Bury, German, born 1946 Ring Date: 1970 Gold and acrylic

Overall: 7/8 × 1 1/2 × 1 1/2 in. (2.2 × 3.8 × 3.8 cm)

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Helen Williams Drutt Collection, museum purchase funded by the Mary Kathryn Lynch Kurtz Charitable Lead Trust, 2002.3661 © Claus Bury Photo Copyright: Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Photographer: Thomas R. DuBrock Additional Copyright Holder (if known):

Claus Bury

Transcript:

For the uninitiated, jewelry, art and craft may seem like three distinct (and perhaps, unfortunately, hierarchical) entities. But Cindi Strauss, Curator of Decorative Arts, Crafts and Design at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, wants us to break down these barriers and appreciate the value of jewelry as an art in its own right. She joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about how she helped MFA Houston establish one of the largest art jewelry collections at an American museum; why jewelry artists should be proud of their studio craft roots; and why wearability shouldn’t be the first consideration when looking at art jewelry. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is the second part of a two-part episode. Today, our guest is Cindi Strauss, the Sara and Bill Morgan Curator of Decorative Arts, Crafts and Design at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas. If you haven’t heard part one, please go to TheJewelryJourney.com. Welcome back.

I remember having a conversation where I did not know what you meant—I know now, but an encyclopedic museum. What does that mean?

Cindi: It means a museum that collects and displays art from antiquities to the present and covers—I’m not going to say all, because one could never say all as in completely—but covers very thoroughly all world cultures. We collect across the board in terms of types of art making, so the MFA in Houston is the only encyclopedic institution in our region. We’re in the south-central region, if you will, so we were founded on the idea of the big institutions that were founded in the late 19th century in the Northeast and Midwest. That was the ambition.

Sharon: Well, it’s Houston. I presume it’s the biggest. You only go for big, I presume. You’re big into crafts in terms of studying. Where do they fit into all of this? Where do you cross the line from jewelry to craft? Is jewelry is a craft? How do you see it?

Cindi: I separate design from craft—these are generalizations, but you can separate the handmade from the machine-made or the industrial-made. There are certainly design objects that have the hand as part of them. I think art jewelry is absolutely part of the studio craft movement. It comes out of that history. It’s a vital history and has to do with material usage and development, handcraft skills, making things on a one-off basis, making one-of-a-kind pieces. Today, of course, we have this wonderful hybridization, which allows for a type of creativity that is unbridled. So, you will have things that have industrially based materials, or people making works in limited editions, but at its heart, it comes out of a studio practice and a studio history.

All of it, as far as we consider it at the MFAH, is art. It’s art in the same way that photography is, that painting is. It’s exhibited on an equal plane, and you see that throughout our new building. There are departments, specific galleries on the second floor. I have both craft and design galleries, but the third floor is completely interdisciplinary, so you get to make those connections and see the dialogue between jewelry and anything else, for that matter. At our institution, it’s a wonderful way to have your cake and eat it too, because the possibilities are endless.

One of the things I have been fortunate with, both with art jewelry and our ceramics collection—because they have both been a part of the institution now for almost 20 years—is that I’m not on a steep learning curve. My colleagues aren’t on a steep learning curve of understanding the tenets of the field and how jewelry connects and crosses over; it just is. That is an amazing place to be.

Sharon: As you were saying that, I was thinking about how you cover this in your mind, let alone physically. There are so many areas you’re talking about.

Cindi: Yeah, and it’s only one part of what I do, because I am responsible, basically, for 20th and 21st-century decorative arts, craft and design. Now, I’m really lucky that we have an endowed position for a craft curator, who was formerly Anna Walker. Joining us at the end of this month is Elizabeth Essner, who may be familiar to some of your audience because she has written on art jewelry and worked on art jewelry exhibitions. That’s terrific, because she is completely dedicated to that material.

There’s another curator in my department; we split the late 19th century and early 20th century material based on our own interests and expertise. She otherwise does the historical material, but she does Art Nouveau; I do Art Deco. She does Arts and Crafts; I do Reform. That 20 or 30-year period when there are so many styles of movements happening, we share that. We have a terrific curatorial assistant who helps, but I love the fact that I don’t work on only one media group or timeframe or one geographic area. It allows me to see more broadly. It allows me to make a lot of connections that I wouldn’t be able to make if I my job description were more solid. Frankly, you never get bored.

Sharon: It sounds very exciting.

Cindi: There’s always more to learn and see.

Sharon: It sounds thrilling to cover all that. I’m wondering; it seems that some art jewelers or any kind of jeweler, like studios jewelers, they might think “craftsperson” or “that’s craft” is a little pejorative.

Cindi: I don’t think so anymore. That was something that—from my perspective and my personal opinion—throughout the birth and few decades of the studio craft movement, it was held in high esteem. There were galleries that showed important painters and sculptors next to ceramists and jewelers and such. In the 80s, when the art world changed dramatically, the go-go 80s, a lot of these divisions started happening. That was when the big “Is craft art?” question came. It did such damage to the field because artists were demoralized; collectors started getting defensive. Looking back on it, it’s clear those questions and divisions did damage to the field.

By the time I was in graduate school in the early 90s, there was a pause on that silo-ing and splitting. So, I did not, from a graduate school perspective, learn any of those divisions. It was all decorative arts. Craft and design was all one field, but I think, certainly in the past 10 years, if not longer than that, that division, that question has been put to rest. I think from an academic perspective, from an artistic perspective, I hope from a collecting perspective, that that has all been pushed behind. It is just art.

If you look at what’s happening with major galleries, they’re showing ceramics; they’re showing art jewelry along with their contemporary art program. In a way, that harkens back to the 70s and 60s. The market prices haven’t quite caught up to where they should be based on the artistic quality of a craft artist. That will, I think, take a little more time. But every other metric, looking at reviews, art magazines, exhibitions, the big galleries that get a lot of press, they’re showing fiber; they’re showing ceramics. They’re even starting to show jewelry. So, I hope everything has moved so far that that question gets put to bed.

I’ve always felt that, in this case, art jewelry should be incredibly proud of its history and its field individually and not spend all of its time worrying about what the larger art world thinks. The larger art world is interested and that’s terrific, but that should not be its only goal. I think it is important and worthy as an artistic movement, statement, something to collect, etc. on its own. A lot of the encyclopedic museums that have been showing and acquiring major collections of art jewelry are validating that, beyond the more specific museums like the Museum of Arts and Designs, formerly the American Craft Museum, or Racine or the Fuller Craft Museum, or a number of different institutions around the country that collect a lot of craft, or museums like the Metal Museum that focuses just on jewelry. That’s an important step forward, also.

Sharon: You’re certainly an articulate champion of art jewelry being not just jewelry, but a medium. So, the Fuller and the Racine are where?

Cindi: The Fuller is in Massachusetts outside of Boston. I can’t remember its exact town. The Racine is in Racine, Wisconsin. The Metal Museum is in Memphis, Tennessee. Then there are a variety of other museums that have shown art jewelry through individual artists’ exhibitions. I’m thinking about San Francisco Craft and Design. It used to be Craft and Design, but now I think it’s called the Los Angeles Contemporary Museum. We, of course, have the MFA Boston. You have Minneapolis, LACMA, Dallas Museum of Art, all with significant jewelry collections in terms of encyclopedic institutions, and there are other institutions that have core holdings.

Sharon: You touched on this, but the question always is: is art jewelry art? It’s always a debate when you’re trying to educate or explain it to somebody.

Cindi: I think that’s the case because art jewelry is wearable, and people aren’t used to thinking that something that is wearable is also art in the way you would display it, whether that’s hanging on a wall or displaying it in glass. That is a personal divide; it’s something people individually have to work through.

There’s no question that it’s art, but I have noticed, in my experience, when people see art jewelry in the museum context, especially women, one of the first things they’re thinking about is, “Would I wear this?” Once you can get people to remove that question from a first, second or third consideration, they can look and experience the work as a piece of art. It’s great for them to think about whether they could wear it, because if you remove the taste question, they’re really looking to see how this piece of jewelry would interact with their body, which is so central to a lot of work in art jewelry. You want that to happen.

What you want to get away from, in terms of experiencing it as a work of art, is taste. Is this my taste? Would I wear this? When we have docent tours or any kind of educational program that centers around art jewelry, this is one of the things we stress. You can, of course, like something or not like that. That’s with everything in a museum and everything in the world, but try to look at a piece of art jewelry without that consideration being foremost. Then work through it as a piece of art being displayed and then, yes, think about how it will work on your body.

Sharon: That’s interesting. My first thing is to look. It’s jewelry. I’ll go for big pieces or big statement pieces. Some of it is too much, but if you do back off, you can look at it as art. Do you think the art world looks at art jewelry as art or thinks about it becoming art, or do you think it’s not going to happen?

Cindi: I think when people encounter it, every collector out there can talk about experiences when they’ve been at an art fair or an opening or a party where they’re wearing a piece of art jewelry and it gets attention. People have questions and they want to know about it. That is an introduction to this field, and it inspires a lot of people to learn about it and collect it. Whether it’s a gallery setting, or a museum, or a booth at an art fair, or an exhibition in space of any type, the key is that people are going to react to it. Whether they like it or not, whether their interest lasts beyond that initial visit, they are being presented with the fact that this is an art form. That does a lot.

I think that’s, in part, why as a field we are always striving to have more opportunities for people to see art jewelry and connect with it, because that will inspire that interest. Everything has its ups and downs in terms of viewing possibilities, the market, etc., but my personal experience, again, is that people are really intrigued by it when they see it. Even if they don’t explore anything further after that initial encounter, it’s still lodged in their memory. You never know when that comes back and becomes a touchstone.

Sharon: That’s interesting. I’d like to ask you a lot more questions. You gave me a lot of food for thought. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us, Cindi. It’s been educational and illuminating, and I’ll have to mull it over.

Cindi: Thank you, Sharon, I appreciate the opportunity. It’s been great fun.

Sharon: Thank you.

Thank you again for listening. Please leave us a rating and review so we can help others start their own jewelry journey.