Episode 170

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- Why designing a bracelet is the same as designing a bridge

- Why jewelry has its own design language, separate from the language of fine art or craft

- How Warren learned about the engineering of jewelry making by doing repairs

- Why the architecture of a piece of jewelry is as important as its visual design

- Warren’s tips for creating beaded jewelry that will withstand the stress of movement

About Warren Feld

For Warren Feld, beading and jewelry making endeavors have been wonderful adventures. These adventures over the past 32 years have taken Warren from the basics of bead stringing and bead weaving, to wire working and silver smithing, and onward to more complex jewelry designs which build on the strengths of a full range of technical skills and experiences.

He, along with his partner Jayden Alfre Jones, opened a small bead shop in downtown Nashville, Tennessee, about 30 years ago, called Land of Odds. Over time, Land of Odds evolved into a successful internet business. In the late 1990s, Jayden and Warren opened another brick-and-mortar bead store – Be Dazzled Beads – in a trendy neighborhood of Nashville. Together both businesses supply beaders and jewelry artists with all the supplies and parts they need to make beautiful pieces of wearable art.

In 2000, Warren founded The Center For Beadwork & Jewelry Arts (CBJA). CBJA is an educational program, associated with Be Dazzled Beads, for beaders and jewelry makers. The program approaches education from a design perspective. There is a strong focus on skills development, showing students how to make better choices when selecting beads, parts and stringing materials, and teaching them how to bring these together into a beautiful, yet functional, piece of jewelry.

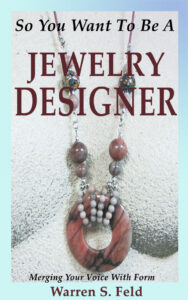

Warren is the author of two books, “So You Want to Be a Jewelry Designer: Merging Your Voice with Form” and “Pearl Knotting…Warren’s Way,” as well as many articles for Art Jewelry Forum.

Additional Links:

Warren Feld Jewelry

www.warrenfeldjewelry.com

Warren Feld – Medium.com

https://warren-29626.medium.com/

So You Want To Be A Jewelry Designer School on Teachable.com

https://so-you-want-to-be-a-jewelry-designer.teachable.com/

Learn To Bead Blog

https://blog.landofodds.com

The Ugly Necklace Contest – Archives

http://www.warrenfeldjewelry.com/wfjuglynecklace.htm

Land of Odds

www.landofodds.com

Warren Feld – Facebook

www.facebook.com/warren.feld

Warren Feld – LinkedIn

www.linkedin.com/in/warren-feld-jewelrydesigner/

Warren Feld – Instagram

www.instagram.com/warrenfeld/

Warren Feld – Twitter

https://twitter.com/LandofOdds

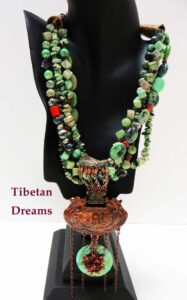

Photos:

Transcript:

Warren Feld didn’t become a jewelry designer out of passion, but out of necessity. He and his partner Jayden opened their jewelry studio and supply store, Land of Odds/Be Dazzled Beads, due to financial worries. But coming to the world of jewelry as an outsider is what has given Warren his precise and unique perspective on how jewelry should be made. He joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about the language of jewelry design; why jewelry making should be considered a profession outside of art or craft; and why jewelry design is similar to architecture or engineering. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is the second part of a two-part episode. If you haven’t heard part one, please go to TheJewelryJourney.com. Today, my guest is jewelry designer Warren Feld. Warren wears several hats. He has an online company called Land of Odds. He has a brick-and-mortar store, Bedazzled Beads, and he’s a jewelry designer. He’s located in Tennessee. He’s been a jewelry designer for decades and has a written a book called “So You Want to Be a Jewelry Designer.” Welcome back.

Can you design a bad piece of jewelry? Can you come up with a bad piece of jewelry?

Warren: Yes and no. When we get into the cognitive issues, I deal with them in my book in detail. It’s a little too scientific for here, but in general, jewelry is organized as a circle. A circle is appreciated as something organized, unified, holistic. A circle in and of itself is beautiful. So, it’s really hard to design something that’s bad. While you can get better and better and better, it’s hard to get worse and worse and worse. It’s much harder.

Sharon: Let’s say I bring in a bunch of beads—I haven’t beaded for a million years—and some silk cord, and I say, “O.K., Warren, what should I do with this stuff?” Can you look at it and see something in it?

Warren: Usually. In that situation, they’re the designer; they have to live with it. I can guide them. I can help them make choices. I can help them narrow things down to two or three, but I try to always encourage them to make the final choice. But in my mind, I usually can do something really neat with it.

Sharon: It’s interesting that you say you learned so much just from taking things apart, seeing how they’re done. I had someone come on here and they were like, “Why did the guy glue this? I don’t understand.”

Warren: Yeah, you learn so much. That was a lucky break, that I decided to deal with repairs. I didn’t care enough about jewelry to say, “Oh, I’ve got to do repairs,” I thought I should do repairs. It was a lucky circumstance that it was one of my interests.

Sharon: Was the book burning a hole in your mind for a long time? Did you feel like, “I have to write this down”?

Warren: It’s really funny you say that. It’s like I wrote the book, and it’s all the stuff out of my head. It’s so great. It’s there in a book, so I don’t have to find it somewhere in my files. I don’t have to think as hard about different concepts. I can just go to my book and there it is. I don’t have to remember.

Sharon: Was it on your mind for a long time, the authorship, putting it all together?

Warren: About 20 years. I struggled, though. I wanted to write a funny book about funny things that happened with the different jewelry designers I’ve met in the store and how they try to solve things. I still might write that funny book, but this was the right book to get all the ideas out and really crystallize things. I was more interested in asking, “What does it take for jewelry designers to see themselves as a profession?” If they don’t see themselves as a profession, if they see themselves only as technicians, then we lose a lot. First off, as technicians, if they’re just following a set of steps and cranking out jewelry, machines can do that. We don’t need a designer. We don’t need the creativity. We don’t need that insight. We don’t need all those different artists’ hands to show what they can do, so we can appreciate a variety of ideas and concepts and interactions. What need is there if they’re technicians?

So, let’s make them professionals, but there’s a lot of pressure not to go in that direction. There’s a lot of pressure in art to keep subsuming jewelry under art and not let it have its own expression. There are a few jewelry design schools in the United States and more abroad, but they mostly teach metalcraft and technique. They really need to teach ideas. We have all these great jewelry designers all over the world who can describe their expression, but we really want to understand it. We want to build upon it. We want to understand how the ideas in their heads resonate, how that gets translated into jewelry, how people respond to their jewelry. We want to be able to articulate that much more deeply than just describing, “These are the materials. These are the dimensions and the measurements. This is the general philosophy of what they’re trying to do. This is the title of the show.” There’s a lot more. I was trying to build that. That was more motivating than writing my funny book. I might write that funny book.

Sharon: That sounds like a funny book, like a different podcast. It sounds like what you’re talking about would be difficult to put into words.

Warren: It is. I’ve had a lot of experience teaching students for a long time over 25, 30 years, so I’m used to translating hard concepts into language that beginners and intermediates can understand and grab onto. When I talk about parts, I give an example of a famous designer who does wrap bracelets, two pieces of leather and beads that go around your wrist, I’d say, two times. She charges $500 per bracelet, and I had the chance to repair many of them. She uses Indian leather, which dries out and cracks, and Chinese fire-polish beads, which is a clear bead with a color coating. The coatings rub off, so the side that faces the skin rubs off. This all happens well within a year, maybe six months. She uses a weak weaving thread that will break. She doesn’t reenforce the beginning and the end, so the weaving threads split at the beginning and the end. You have to reenforce the end so that doesn’t happen. It’s an architectural thing. For $500, she can use great leather, fire-polish beads, a nylon bead cord. She can do a silk wrap on each end to secure the ends, so they don’t split down the middle. She can still charge $500 and make a killing. It’s easy to come up with examples like that.

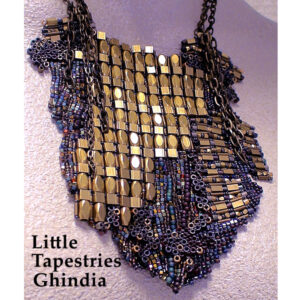

I can show you a piece I did. I did the piece as a series of columns, and the columns are connected with a hinge. You can’t really see it in the piece, but they’re hinged. What I wanted was, no matter what the body type, that the necklace would always be the right shape because it’s columns and hinges. It wouldn’t look weird. It wouldn’t create a bridge. It would always take the shape of the body. I pictured that a person might want to wear it close to the neck or lower on the breast, so it has a chain that’s adjustable.

I pictured the person wearing it to always want to capture someone’s eye, no matter what direction they’re looking at it, from the side, from the back. So, along some of the sides, I strategically wove in red Austrian crystal beads. They’ll catch your eye, but you don’t see it in the piece. The piece is basically blue. I used some brass beads that reflect light when white hits the piece. I used some glass beads that absorb light. Again, when I’m talking about design and architecture, I’m thinking about people viewing it. I’ve done all these things as examples of what people can think about. In the book, I’ve put a lot of this into English as best as I can.

Sharon: Most of the books I’ve looked at have been jewelry history or how-tos. I was thinking about this when I read your book, because you said that a piece of jewelry needs to be orchestrated from many angles, which is what you were just talking about. I remember a jeweler—this was years ago—who was talking about the fact that jewelry requires a lot of engineering. I never thought about that before in terms of bracelets not turning or things like that.

Warren: There is really no difference between making a bracelet and designing a bridge. It’s a different scale. You tie one end to the other. It’s got to look good and fit in a community. You’ve got to worry about your materials and how they handle stresses and strains. It has to be secure. It’s got to be durable. So, there’s really not much difference between the two. There’s all this architecture and engineering involved.

A lot of people don’t learn that. Most people learn a technique and they just do it, but technique has a part of it that helps you maintain a shape, and another part of the technique helps you maintain what I called movement and flow. Sometimes you have to be tighter or harder, sometimes not as hard, in order to achieve both maintaining the shape and maintaining the ability of that shape to adjust to all these forces and move and flow and feel comfortable. How many how-to books talk about that? They don’t.

Sharon: No, that is true.

Warren: In every technique the students learn that. I show them and force them to touch it. I personally touch on the results of different techniques and tell them what’s going on, what it feels like, what you can do. If it’s loose in one direction and tight in the other, you can’t make a curve. They never even thought about that, and now they do. They’re forced to think about that. When you teach a technique, I think it’s important. For a teacher to teach a technique that way, they have to be conditioned to teach that way. There’s no guide in jewelry design. There’s no academic base, a foundation for someone to ask those questions or be triggered to think that way. That’s one of the things I was trying to do in my book when I wrote the last chapters, where I teach all this stuff. You have to know.

I’ve had to train a lot of teachers through my education program. It’s really hard to do because at first you think, “I can make as much money not doing this work. I have to give them those instructions and just sit there.” I can’t do that in my program. I want the teachers to break the task up into little pieces and explain what this little piece of the task is trying to accomplish, so the students can know how to vary the technique as they’re going through the project and change the outcome if they want something that keeps its shape, moves shapes and feels comfortable. So, I have to train a lot of them. I have my strategies for training them. It’s really hard to do that, but I think very necessary. If jewelry becomes a profession, it’s necessary. We need to train jewelry designers as designers, not as craftspeople or artists.

Sharon: That’s a good point because there are so many “jewelry designers” today. They were doing something else before and decided to design jewelry, and they don’t have any training. They just said, “Oh, I’ll put these two pieces together.”

If you walk through a trade show or some sort of jewelry show, what are you looking for? How are you evaluating pieces?

Warren: I have enough experience in all these different techniques to spot what’s good and what’s bad. I will lead a tour of people on a shopping trip at a company and say, “This is good,” and I can show them why, and “This is not.” They end up spending thousands of dollars on really good stuff that they would have never gotten anywhere else. I can spot it because I make it. I made it. I’ve hidden the mistakes. I’ve had the most horrible problems happen with things falling apart, so I can spot it.

It’s the choice of materials. It’s the choice of construction. When you construct something, you have to go in with a support system, which is like a joint. You’ll see someone’s necklace turned around because things turn in the opposite direction from where they move. What turns to the left turns to the right. That’s not natural. That’s bad design. If you built a support system with joints, that never happens. If you take an S-clasp, a figure S, it has to have two solder rings, one on each side. If you’re using cable wire and crimp beads, you don’t crimp all the way up the clasp; you leave a little bit of a loop, so they have a ring loop on one side, a ring loop on the other. That’s four support systems for joints. An S-clasp always needs four joints, and the necklace will never turn around.

Sharon: It’s really important. I’m thinking it will eliminate a lot of what I have in my collection. Do you use the book as a guide in your classes?

Warren: The book is being pre-tested in classes. We ran a series of jewelry design classes. There were 27 topics. We’ve done it several times. On each topic you hear students’ questions. There are questions I have, how they answer, some resolution. A lot of the material in the book emerged from those discussions.

Sharon: What was your purpose in writing it? Was it to gain credibility or get your knowledge out there?

Warren: The book was really to push those ideas out there, to encourage and force more professionalization of the field and the discipline of jewelry design. The ideas are out there, but they’re not organized. From my experience, most people are unaware of the ideas about design. They’re very focused on the individual and unaware of all the architectural, like with the S-clasp. If someone comes into the store and their necklace keeps turning around, I can fix it so it could never turn again. They have something with either some rings or loops. It could have a hinge with it, and you can add a lark’s head knot, which is very loose and creates a lot of joint and distance support. You also have an overhead knot, which gives a little less support, but still a lot of joint support. A square knot is even less support, a glued knot, zero support.

If you have a piece where you’re gluing a lot of the knots, it’s going to break. It can’t take the stress. If you’re doing pearl knotting, whatever you’re doing, you want to minimize the use of glue. You have to glue at least one knot in pearl knotting, but that’s it. That’s as much support as I want to take away. Knots not only protect the pearls, but they absorb all the stresses and strains on the necklace from movement, instead of the stresses and strains ending up on the pearls, where it can crack. If they’re unglued and there’s an overhead knot to absorb all the stress and strain, your piece will break, but you won’t ruin your pearls. When people wear pearl knotting, they don’t worry about the architectural issue of stress and strain. You never see that in a book about hand knotting, but that’s one of the major reasons you have the knots, to preserve your materials and the piece as a whole. So, let’s get the information out there.

Sharon: That’s a very interesting point, a good point to think about. Warren, thank you so much for being here.

Warren: I appreciate it, thank you.

Thank you again for listening. Please leave us a rating and review so we can help others start their own jewelry journey.