Episode 164

What you’ll learn in this episode:

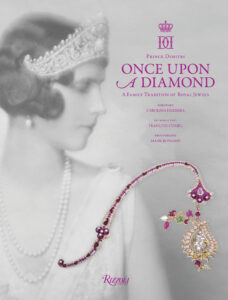

- The surprising stories Prince Dimitri discovered while compiling material for his book, “Once Upon a Diamond: A Family Tradition of Royal Jewels”

- How decorative and fine arts have influenced jewelry throughout history

- Why paisley is an enduring motif in jewelry

- Why mixing high and low jewelry and fashion has always been chic

- How Dimitri’s ancestor Catherine the Great created the royal uniform we recognize today

About Prince Dimitri

Prince Dimitri founded his company in 2007 after sixteen years as Senior Vice President of Jewelry with Sotheby’s and later as head of Jewelry at Phillips de Pury & Luxembourg auction houses.

Dimitri’s love of jewelry dates from his childhood and unique heritage of a family where the heads of European Royalty were closely tied together in an era of extreme opulence, beauty and culture all over Europe. He began designing jewelry in 1999, with a collection of gemstone cufflinks that was sold at Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Fifth Avenue. He also designed a line of women’s jewelry that was sold at Barneys New York and Neiman Marcus. He has designed for Asprey’s in London and done special lines for other American companies. With his own jewelry company he has been able to realize his own vision in his love of gemstones; the juxtaposition of unusual materials and color; imaginative forms and paying attention to detail and to superb craftsmanship.

Additional Resources:

Photos:

Available on TheJewelryJourney.com

These pieces were all made by Squaremoose studio in NYC https://squaremoose.com/

Transcript:

Growing up surrounded by the world’s most beautiful jewels, it’s no wonder that Prince Dimitri became a jewelry designer known for his gemmy creations. After working in the auction world for many years, he launched Prince Dimitri Jewelry, which offers a range of jewels from affordable to six-figure masterpieces. He joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about how jewelry became a symbol of royalty; the most memorable pieces that came across his desk at Sotheby’s and Phillips; and where royal jewelers throughout history found inspiration. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. This is a two-part Jewelry Journey Podcast. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it comes out later this week.

Today, my guest is Prince Dimitri of Yugoslavia. After more than a decade in the auction world, rising to the top of the jewelry ranks, Prince Dimitri took his love of gems and launched Prince Dimitri Jewelry. He is also an author, having written “Once Upon a Diamond: A Family Tradition of Royal Jewels.” The book has been described as an extraordinary family scrapbook. It has photographs of his relatives, who are celebrities and royalty, showing them wearing their jaw-dropping jewels. It weaves in stories of his illustrious family background and the history that goes behind the photographs. We’ll hear more about Prince Dimitri and his jewelry as well as his jewelry journey today. Prince Dimitri, welcome to the program.

Prince: Thank you. Hello, Sharon. So nice to see you.

Sharon: Nice to see you.

Prince: I heard so much about you.

Sharon: Dimitri, I’m going to let you tell everybody what your official name is because I could not pronounce it. I saw different variations. Go ahead.

Prince: It’s a Serbian name. It’s pronounced Karageorgevich, and it’s written with letters that don’t exist in our alphabet.

Sharon: I didn’t realize that. It’s interesting; in everything I saw about you, it gave your name, but I didn’t realize it was Serbian. Tell us about your jewelry journey.

Prince: It all started as a child. I was obsessed with gems, totally fascinated when I saw my mother and my grandmothers wearing jewelry. When we were in the street and there was a jewelry store, I had to go in and look, and I would stare at the showcases. It never left me. I think I was born with it. It’s my passion in life. I joined Sotheby’s in 1984 and I stayed there until 2001. Then I was at Phillips for three years. Little by little, I started designing, and now it’s all I do.

Sharon: I thought it was interesting; some of the material I read said you started making jewelry because you decided you’d seen everything there was to see in jewelry after so long in the auction world. Tell us a little bit about that.

Prince: It’s not exactly like that. I started designing cufflinks when I was at Sotheby’s totally by chance. I had no idea I could design anything or that I was slightly creative. I was a gemologist and expert. I appraised jewelry, and that’s all I did. Then a friend of mine had some cufflinks he had made in Brazil with some lovely stones, but a very ugly mounting with thick claws around it. I looked at it and I thought, “You know, I love those stones, but those big, thick claws around it are so clumsy. You need to remount them.” He said, “How should we remount them?” All of a sudden, my mind went blank. I saw a little hole, and I said, “That’s it. You’re going to drill a hole in the center of the cufflinks. In that hole, you’re going to set a little diamond or a ruby or an emerald or a sapphire. It has to be a precious stone, one of those four. That will be how you mount it, through the stones. What you’ll see on your shirt will be that lovely, emerald-cut aquamarine with a little stone in the center.” Slick, clean, very gemmy, very chic, I thought. He did it, and it worked beautifully.

He said, “Why don’t we do a collection like that?” Long story short, we did the collection. It ended up at Bergdorf, at Saks. Little by little, I said, “Let’s make some rings and some bracelets and some necklaces on the same principle. All of it,” and we made all that. We were doing trunk shows on the side, as I was still at Sotheby’s then, and little by little, it took on a life of its own. Then I was given an offer to join Phillips with a group of other people. It was at the time when Sotheby’s was going through major changes and nothing was very happy there anymore, so I thought, “Why not?” That didn’t last very long, the Phillips adventure, so I continued.

Then, I was approached by a wonderful man who was called Salvador Assael, the king of pearls in those days. After the war, he had convinced all the big houses that black pearls were not black because they were dirty; they were black because it was a beautiful color. He finally opened their eyes. He told me the story of how they would look at the pearls and say, “But these are black pearls. They’re dirty. Pearls are supposed to be white,” and he told them, “No, open your eyes. Look at this. This one is a green one. This one is a pinkish one. This one is a peacock one with mixes of green and purple,” and they loved it. He became the number one wholesaler of pearls.

Sharon: Is that Assael?

Prince: Assael, yeah.

Sharon: Wow!

Prince: He’s very famous. He called me one day. He said, “You know, I love the old jewels and everything you make.” It was after 9/11. The market was not doing well for jewelry anywhere. He said to me, “I can’t sell anything anymore because there are only so many strands of pearls people want. Do you think you can design a collection for me? More importantly, do you like pearls?” I said, “Yes, I absolutely love pearls.” We made this collection, and before you knew it, we were in every Neiman Marcus in America except three or four of them, I think. We were in 35 Neiman Marcuses. We were the number two seller at Neiman Marcus and it became a huge success.

Then I met my business partner who put me in business to be a serious company. That was 2008, so things didn’t work as well as I wished. I had to go on my own because he couldn’t funnel any more into it, and now that’s all I do. I’m back at Neiman Marcus in Dallas, but the bulk of my business now is one-of-a-kind pieces. That’s what I really like. As I say in the preface of my book, I like the concept of alchemy. Bring me some lead; I will turn it into gold. All my friends look into their drawers and find these old stones and granny’s pearl necklaces that they can’t wear because they’re so dated and all of that. Sometimes they bring me bags of things that are totally unrelated and I do the magic. Half of the jewels in the book are made like that.

One of the typical examples: I was in Southampton with a friend. We were picking up pebbles on the beach together one day in August. We go home. She shows me these diamond earrings she wants me to remount, these little strings of diamonds that are badly made and boring. I went into the bowl where we had placed all the pebbles. I picked four of the most similar ones, and I said, “Here. This is where your diamonds are going. This is going to be your necklace.” She thought I was completely crazy. She said, “I know you are original and you have ideas, but—”

Sharon: You were mixing pebbles and diamonds? Is that what you were doing?

Prince: Yes. She said, “You’re going to have to explain this to me.” I said, “I will. I will do a drawing for you, and you will make your decision.” So, I did the drawing. I get a phone call from her a few days later. She goes, “I love it. I need this necklace more than I’ve ever needed a piece of jewelry.” It’s featured in the book; you’ll see it.

Sharon: How did the book come about? Did you want to write the book? Did Rizzoli come to you?

Prince: The same way the first cufflinks came to me: totally by chance. It’s one of the miracles of modern technology. It’s called Instagram. I put all my jewelry on Instagram, but I have tons of old photos from the family, and I post them and write fascinating stories of what all these people have done. For instance, how my great-grandmother saved the life of Albert Einstein; how Adolph Hitler kidnaped the sister of my grandfather and had them killed in a concentration camp. Some of them are beautiful stories; some are very, very tragic, but there are many of them. Somebody from Rizzoli sent me a message on Instagram saying, “I love your Instagram. We should make a book based on that concept. I need to talk to you.” Long story short, it took two and a half years, and here we are.

Sharon: Somebody should put together a book of all the stories of everything that’s come from Instagram, because people have started jewelry lines and written books from it. It’s really launched a lot of people. Was it hard for you to gather all the material, or did you already have it?

Prince: I already had all the material. What I didn’t have, my mother had. Also, some uncles and aunts and relatives had it, so that was easy. The difficult part was how we were going to make it work. We had to put the chapters in order. It was like a puzzle. We had everything on the floor in our minds, with the different chapters and stories and everything. Little by little, it came together. Everybody had a great idea. I had great ideas.

They lady who wrote the book with me had a great idea. She was a fantastic fact checker. She discovered, for instance, that—one of the stories I tell is how, before the war, my grandmother, then Crown Princess of Italy, had discovered Maria Montessori of the famous Montessori School. She decided she loved that program so much, because it was so modern and interesting and ahead of its time, that she wanted to create her own Montessori School at the royal palace for her children and children of the nobility.

My mother told me, “Yes, it was fantastic. Here’s the photo.” The school was in the Gallery Uffizi in Florence, which had been turned into a palace one year before, in 1942. She said, “Yes, and Maria Montessori was so nice. I remember her.” Well, it was a fictitious memory my mother had because she was eight years old. We found out through fact checking that Maria Montessori was actually in India for eight years at the time. The person she met was the associate of Maria Montessori who founded the school with her. My mother assumed that, because her mother was who she was, it was actually Maria Montessori herself who came, but it wasn’t the case. We discovered lots of stories like that.

Sharon: Interesting.

Prince: We discovered that my grandmother’s famous Cartier jewelry was not Cartier jewelry. I pressed and pressed the wonderful gentleman at the Cartier archives, the poor thing. I tortured him so much that he had to do three months of research to find out that it was my great grandmother, the Grand Duchess Vladimir of Russia, who came to Cartier to buy some things and asked him if they could repair this tiara she had in her bag. It was a tiara from Chaumet, and nobody knew it. In every history book, it’s listed as the Cartier Tiara.

I had just enough time to jump on my phone and call the editor at Rizzoli when we were already in full print. I said, “This is what’s going on. We need to change the story.” They said, “You can delete the word Cartier. That’s all I can do for you. It’s too late.” We were in the middle of Covid. The paperwork was done in Bologna, which was the center of printing in Italy. “That chapter is going to be printed six hours from now, so let me hang up and call them.”

Sharon: Is that what you did? You just didn’t use the word?

Prince: We just removed that, yeah. We couldn’t say anything more, but I speak about it all the time. So, now people know.

Sharon: Interesting. I’ve seen the book and I’ve looked through it, but I don’t come from an illustrious background like you do. My ancestors were not royalty, so I didn’t relate to it as much, but now this humanizes it.

Prince: Yes. There are 16 pages of Romanov photos that have never been published before because I owned the four albums they were in, and I’ve never shown them to anybody. These are really interesting because it shows them in day-to-day life. They are in the south of France. They go to a spa in Gautreau, Seville, famous for its water. They visit the house of Joan of Arc. It’s really interesting.

The most fascinating series of photos is the second Olympic Games in history, photographed by my great grandmother. It’s all there in the book. There were also photos in Venice and photos in Spain at the bullfights, but we decided not to show the bullfight because it could be controversial. In those days, it wasn’t.

Sharon: You’ve lived all over the world. Prior to coming to the auction world, you went to school in Switzerland, then France?

Prince: I was in law school in Switzerland for a while, then in France. Then I did law school in Paris.

Sharon: When did you do GIA?

Prince: When I came to New York. When I finished law school, I had so many friends already in New York. New York was this magic world far away from us. There was something very exotic about America and New York. It was quite fascinating, so I decided to come here and finish my law studies. I had my degree already, but I thought it would be a good idea to do a training program on Wall Street, which is what lots of European people did. So, I did that on Wall Street for almost a year. It was very interesting. I learned a lot of things, but I wasn’t particularly ready to make it a career. There was an opening at Sotheby’s that I found out about, and that’s how it happened.

Sharon: Was it a huge decision, or was it a natural segue to go into that world from the world you were in, the business world?

Prince: Yes, it was a big decision. It was a very exciting decision. It was a logical thing to do because I have this Renaissance mentality. I think one should know about everything in life. I felt that with a law degree and a kind of Wall Street degree, which is a Series 7—it’s the exams you take to become a stockbroker—I thought, “I’m well educated enough to do what I really like, which is gemology and stones and jewelry and all of that.”

I worked at Sotheby’s right away. I knew enough about jewelry that I could become an expert right away, in the sense that I needed to learn gemology at the GIA, which I went did by following the prices in the market. Pretty quickly I moved up and became after six or seven years, I think, a senior vice president for the company.

Sharon: What was it about the auction world combined with jewelry that attracted you?

Prince: The amount of jewelry we sold every day, that was the exciting part. For every auction you see, the catalogue you see four times a year in New York, three times a year in Geneva, four times a year in London, and, in those days, also in Hong Kong, that catalogue represents the tip of the iceberg of what comes in and out the doors of Sotheby’s. Every day, it was mountains of jewelry. It was so exciting to see so much. I’m very impatient. I want to see a lot. One diamond that’s there day after day if you work in a shop is not exciting enough for me.

Sharon: You need the constant turnover and attraction.

Prince: Yes. That was great. One day we discovered, literally in a shoe box in a bank vault on Park Avenue, one of the most famous Cartier tiaras. The same one is in one of the Cartier books today. The lady who had it had no idea. She said, “I have this funny thing that goes on the head from my grandmother. Do you think it’s worth anything?” I was like, “Yes! It’s fantastic.”

Sharon: Wow! What else is in shoe boxes that we don’t know about, right?

Prince: There were lots of things like that. My most beautiful story from Sotheby’s, I have to say, was when this poor lady came in. She was a bag lady, literally, in tears and very nervous. I felt there was something going on there. She told me the tragic story of how her husband had divorced her, took all her money, and she had literally one little sapphire ring. She was hoping to get $2,000 to just be able to pay her rent or she was going to be evicted. She was going to be on the street. She starts crying and crying, and she said, “Do you think you can loan me the money?” I said, “Well, can I please see the ring?” She looks at me and goes, “Here it is. Do you think I can get maybe $10,000? Would that be possible? And you could loan me $2,000?”

I take a look at it. It is the most beautiful Kashmir sapphire I saw in my entire life. I said, “I think I can get more. Let me speak to my boss for the loan. Let me see.” I call everybody. I said, “Guys, you won’t believe this.” I tell them the story. They all look at the stone and everybody says, “Oh, my god! We’ve never seen a stone like that.” My boss says, “You know we don’t loan money against one piece.” I said, “John, she thinks it’s worth $10,000. Let’s offer her $75,000 to $100,000 for the ring and let it sell for over $200,000.” He goes, “Fine.”

I go back in the room with a check with me. I said, “Listen, it’s your lucky day. That is a lovely ring. I think we can put an estimate of $75,000 to $100,000.” She almost fainted. She goes, “Oh, my god!” Three months later, she comes to the auction. We opened the bid at $75,000. Before you know it, the hammer falls, and it sells for $380,000. She is sitting in front of me sobbing and crying, and then all of us start crying because we knew the story. It is a lovely story because we really changed the life of somebody.

Sharon: That’s true. You did the change her life, it sounds like. From there you moved to Phillips. From Sotheby’s, you moved to Phillips?

Prince: Yeah.

Sharon: And you were head of the jewelry department there?

Prince: Yes.

Sharon: Where were you when the man from Brazil came to you with the first cufflinks?

Prince: I was at Sotheby’s then. It was in 1997. It was 40 years before I left Sotheby’s, so I was starting that process little by little then.

Sharon: In your jewelry, you barely see the jewelry part; you see the gem. Is it the gems that are talking to you?

Prince: Both. I love that. A lot of my jewelry is very gemmy, like you say. You’re absolutely right, but a lot of it based on whimsical ideas, unusual materials like the pebbles from the beach or even rubber cords. I do things mounted on leather, Damascus steel, oxidized bronze, oxidized silver. 24-karat gold I use a lot. I do all sorts of things. The other source of inspiration is the shapes, shapes as you see them in decorative arts of every culture in the world.

That was the philosophy of Cartier. He instructed, already in the 19th century, the designers who worked for him to look at the decorative arts and to travel and take notes and make drawings of everything they saw, because that was the basis for all sorts of things. In the 19th century, there was a very famous book written, which is called “The Grammar of Ornament.” “The Grammar of Ornament” is a visual dictionary of every artistic style that ever existed in history in any country in the world. It’s absolutely fantastic, and I’ve gotten tons and tons of ideas from there. So did the people at Cartier at the beginning.

For instance, the Edwardian period of Cartier, it coincided with two things: when they rediscovered the Louis XVI decorative arts style with the garlands—it was called the garland style—and the introduction of platinum. Platinum in the old days was not considered a precious metal; it was for industrial applications. Then, when they studied it, they realized how hard it was and how white it was. So, it quickly replaced silver.

If you look at tiaras made with silver, which are the oldest ones from the first half of the 19th century, they are very heavy. They are lovely, but there’s something about them. With the introduction of platinum, Cartier was able to transform them into literally a spiderweb, completely ethereal. That’s when they double in size. They’re ten times as thin and you can put twice the amount of stones. It sits like an aura on your head. That is what gave them the impetus to create the garland style, the classical Art Deco that mutated into Art Deco. At the time, platinum became such a success that it became seven times more expensive than gold.

Sharon: Wow!

Prince: It’s interesting, yeah?

Sharon: Yes, very.