Episode 156

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- Why people get so concerned with categorizing art, and why some of the most interesting art is created by crossing those boundaries

- How Joy balances running a business while handmaking all of her pieces

- What noble metals are, and how they allow Joy to play with different colors

- How Joy’s residences in Japan influenced her work

- How Joy has found a way to rethink classical art and confront its dark history

About Joy BC

Joy BC (Joy Bonfield – Colombara) is an Artist and Goldsmith working predominantly in Noble Metals and bronze. Her works are often challenging pre-existing notions of precious materials and ingrained societal ideals of western female bodies in sculpture. Joy BC plays with mythologies and re-examines the fascination with the ‘Classical’.

Joy, a native of London, was profoundly influenced from an early age by the artistry of her parents – her mother, a painter and lithographer, her father, a sculptor. Joy’s art education focused intensively on painting, drawing and carving, enhanced by a profound appreciation of art within historical and social contexts.

Joy BC received her undergraduate degree from the Glasgow School of Art and her M.A. from the Royal College of Art in London. She has also held two residencies in Japan. The first in Tokyo, working under the tutelage of master craftsmen Sensei (teacher) Ando and Sensei Kagaeyama, experts in Damascus steel and metal casting. She subsequently was awarded a research fellowship to Japan’s oldest school of art, in Kyoto, where she was taught the ancient art of urushi by the renowned craftsmen: Sensei Kuramoto and Sensei Sasai.

Whilst at the RCA she was awarded the TF overall excellence prize and the MARZEE International graduate prize. Shortly after her graduation in 2019 her work was exhibited in Japan and at Somerset house in London. In 2021 her work was exhibited in Hong Kong and at ‘Force of Nature’ curated by Melanie Grant in partnership with Elisabetta Cipriani Gallery.

Joy Bonfield – Colombara is currently working on a piece for the Nelson Atkins Museum in the USA and recently a piece was added to the Alice and Louis Koch Collection in the Swiss National Museum, Zurich.Additional Resources:

Joy’s Website

Joy’s Instagram

Photos:

‘Frangere (Demeter)’ 2022.

18kt recycled yellow gold with champagne, honey and white diamonds pendant & handmade chain

4 cm length pendant

40 cm length chain (handmade)

Edition of 7 + 1AP

Unique within the series

My ‘Ruin-Lust’ works explore the allure and fascination of ruins. Recalling lost civilisations, and certain demise of our own. The also give rise to dreams of futures born from descruction and decay.

Many of the surviving artefacts from ancient Rome and Greece are no longer intact. Sculpted images, for example, are missing limbs or facial features. These losses reflect their personal history. They are also an intrinsic part of their beauty and continuing appeal. The slow picturesque decay and abrupt apocalypse ruins are both captivating and beguiling. This piece in particular is celebrating breakages, failures, scars and stress lines. These works survived centuries, broken, missing parts, and yet they retained their enigmatic presence. Their breakages somehow make them even more beautiful.

Demeter (Ceres), the green goddess of plants and fruits, agriculture and fertility. ‘Rich-haired Demeter…lady of the golden sword and glorious fruits (Homeric hymn to Demeter). Demeter is a very old goddess, who’s name means ‘earth-mother’. Perhaps the most famous of Myths associated to her is that of her searching for her daughter Persephone, who was abducted by Hades. The adduction also revealed the power of Demeter. Demeter Threatening to permit nothing to grow on earth, and for mankind to perish, forced Zeus to negotiate the release of Persephone. However, Hades reluctant to let go of anyone who enters the dark relm, let alone is beautiful wife, he tricks Persephone into eating some pomegranate seeds. This ties Persephone to be doomed to stay in the underworld. Eventually a deal is brokered that Persephone would stay with Hades for part of the year, and in spring would rejoin her mother on the earth above.’

‘Precious Tear’

Each piece is unique.

2.5cm length

925 silver, recycled 18k gold and natural teal sapphire.

This is an ongoing body of work in my exploration of Tears and how I believe they are precious. By transforming an ethereal liquid tear into a hard stone sapphire, I am putting emphasis on the strength it takes to show one’s vulnerabilities. The wearer by engaging with this ‘totem’ becomes the owner of their vulnerability and honestly confronts the aspect of ourselves we often ignore or suppress.

This is an ongoing body of work in my exploration of Tears and how I believe they are precious. By transforming an ethereal liquid tear into a hard stone sapphire, I am putting emphasis on the strength it takes to show one’s vulnerabilities. The wearer by engaging with this ‘totem’ becomes the owner of their vulnerability and honestly confronts the aspect of ourselves we often ignore or suppress.

There are three types of tears, ones secreted to keep the eye lubricated and free of dust, ones to remove particles when the eye becomes irritated (think of cutting an onion), and ones that fall when we feel emotional stress, pleasure, anger, suffering, mourning, or physical pain.

Whatever the type of tear, in my view, they are all precious – and even more so in a moment of empathy or as an expression of mourning for a loss of someone who was important to us. There is even a type of butterfly in the amazon rainforest that survives by lapping up the salty tears of turtles.

This is an ongoing body of work in my exploration of Tears and how I believe they are precious. By transforming an ethereal liquid tear into a hard stone sapphire, I am putting emphasis on the strength it takes to show one’s vulnerabilities. The wearer by engaging with this ‘totem’ becomes the owner of their vulnerability and honestly confronts the aspect of ourselves we often ignore or suppress.

There are three types of tears, ones secreted to keep the eye lubricated and free of dust, ones to remove particles when the eye becomes irritated (think of cutting an onion), and ones that fall when we feel emotional stress, pleasure, anger, suffering, mourning, or physical pain.

Whatever the type of tear, in my view, they are all precious – and even more so in a moment of empathy or as an expression of mourning for a loss of someone who was important to us. There is even a type of butterfly in the amazon rainforest that survives by lapping up the salty tears of turtles.

Hypatia (ring)

Recycled 22kt yellow gold, Recycled Platinum, 18kt recycled white gold with color D/E natural diamonds

3.5cm length portrait

Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Unique within the series

Hypatia was force of nature. A Greek Philosopher and Mathematician. A woman who was written about by Plato in a patriarchal society.

In previous work, I have explored the hidden histories of forgotten female heroes, creating miniature-monuments in their honor. This ring is to celebrate and honor Hypatia – but also to protest against violence to woman. The historical recurrence of violence to women, for simply being a woman, is barbaric. Her portrait is carved and cast into 22ct yellow gold, welded into a platinum shank with Joy’s signature ‘Hewn’ texture which originates from her lineage which dates back to 12th century stone masons. 22ct gold is synonymous with ancient Greek Jewellery. The platinum and diamond tears are strong, noble materials that resonate with the subject.

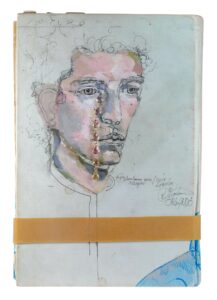

‘Orlando’s Tears’.

25.5cm x 18cm x 4.5cm.

One of a kind.

Ink, paint, grants anatomy book, 18ct yellow gold and sapphires. 2019

Description:

The joyous tears, which subtly transcend from lilac to yellow, solidify a moment of change. The tears detach from the book to form a single earring. The inside of the book is carved into a skull because it is my belief that in whatever skin we are in, we are all the ‘same’.

For this piece, I was inspired by Virginia Woolf’s novel, ‘Orlando’. In it, the protagonist lives through several centuries and changes sex from man to woman. When Orlando changes, she points out that nothing has changed apart from her sex. This was quite a statement in 1928 and is still incredibly poignant and relevant today.

I chose to create an earring because during the time of the Elizabethan courts, which is where part of the novel is set, it was the fashion to wear one earring.

Transcript:

While others are quick to classify artists by genre or medium, Joy BC avoids confining her work to one category. Making wearable pieces that draw inspiration from classical sculpture, she straddles the line between jeweler and fine artist. She joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about why she works with noble metals; the exhibition that kickstarted her business; and how she confronts the often-dark history of classical art though her work. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. Here at the Jewelry Journey, we’re about all things jewelry. With that in mind, I wanted to let you know about an upcoming jewelry conference, which is “Beyond Boundaries: Jewelry of the Americas.” It’s sponsored by the Association for the Study of Jewelry and Related Arts, or, as it’s otherwise known, ASJRA. The conference takes place virtually on Saturday and Sunday May 21 and May 22, which is around the corner. For details on the program and the speakers, go to www.jewelryconference.com. Non-members are welcome. I have to say that I attended this conference in person for several years, and it’s one of my favorite conferences. It’s a real treat to be able to sit in your pajamas or in comfies in your living room and listen to some extraordinary speakers. So, check it out. Register at www.jewelryconference.com. See you there.

This is a two-part Jewelry Journey Podcast. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it comes out later this week. Today, my guest is the award-winning artist and goldsmith Joy Bonfield-Colombara, or as she is known as an artist and jeweler, Joy BC. She is attracted to classical art. She interprets it from her contemporary viewpoint, and her work has been described both as wearable art and as miniature sculptures. We’ll learn all about her jewelry journey today. Joy, welcome to the program.

Joy: Thank you for having me, Sharon.

Sharon: So glad to have you all the way from London. Tell us about your jewelry journey. You came from an artistic family.

Joy: Both my parents are artists. My mother is a painter and lithographer, and my father is a sculptor. So, from a really young age, I was drawing and sculpting, and I thought this was quite normal. It was later that I realized my upbringing was perhaps a bit different from some of my friends or my peers.

Sharon: Yes, it’s unusual that I hear that. They weren’t bankers. Was it always assumed that you were going to be an artist or jeweler?

Joy: Not at all. The fact that my parents were artists, I saw a lot of their struggle to try and place themselves within our society. They both were part of the 1968 revolution. My mom is actually from Italy. She left a tiny, little—not a village, but a small town called Novara which is near Verona and Turin, when she was 16 years old. She came to London and fell in love with London. She went to Goldsmiths School of Art, where she met my father. My father is English, and his ancestors were stonemasons from the Isle of Purbeck. So, they both met at art school, and it was much later that they had me.

As I grew up, they were incredibly talented individuals. They also struggled with how to live and survive from their artwork. As I grew older, however, as much as I loved the creative world I’d grown up in, I was also trying to figure out which pathway was right or was going to be part of my life. I didn’t necessarily want to be an artist. For a long time, I wanted to be a marine biologist because I was really good at science, in particular chemistry and biology, and I really loved the ocean. I still love the sea. Swimming is the one sport I’m good at, and I find it fascinating. I still find the sea as a source of inspiration.

So no, it wasn’t an absolute given; however, as I got older and went through my education, it became evident to me that was the way I understood the world and the spaces I felt most natural in. I’m also dyslexic. I used to be in special class because I couldn’t write very well, but my dyslexia teacher said, “You’re smart. You just have a different way of seeing the world.” I was always imaginative. If I couldn’t write something, I would draw it or make it, and I liked the feeling that would create when someone else lauded me for it. Immediately, I had this connection with the fact that I could make things that people thought were interesting.

So, I studied science and art and theater, and then I went off to travel to Cuba when I was about 18, before I moved to Glasgow. When I was in Glasgow in Scotland, I saw The Glasgow School of Art degree show, and I was taken aback by the jewelry and metalwork show in particular. I don’t know if you know the Rennie Mackintosh School of Art.

Sharon: No.

Joy: It’s a British Art Nouveau building. In Scotland, it was part of the Arts and Crafts movement. It was a school that was designed by Rennie Mackintosh. He’s a world-famous architect.

Sharon: Is that the one that burned down?

Joy: Yes, that year. I was actually there the year the school burnt down. I went to The Glasgow School of Art and I loved it. I did three amazing years there, and in my second year, I was awarded a residency to go to Japan. We had our degree show and we were preparing for it. The night before the fire, I took all of my works home. I don’t know why. I was taking everything home to look at before we had to set up for the exhibition, and the school burnt down. At the same time, I had three major tragedies in my life. My best friend passed away; the school burnt down; and my boyfriend at the time had left me. I went through this total mental breakdown at the point when I was meant to start my career as an artist. I was offered the artist residency in the jewelry and metalworking department.

When Fred died, I was really unwell. A friend of mine had offered that I go to New York. I ended up having a bike accident, which meant that I was in intensive care. I couldn’t work for three years. It was actually two friends of my family who were goldsmiths who gave me a space to work when I was really fragile. It was through making again and being with them that I slowly built back my confidence. That was my journey from childhood up right until the formals of education. These three events really broke me, but I also learned that, for me, the space I feel most happy in is a creative one, when I’m carving.

Sharon: Were you in the bike accident in New York or in Glasgow or in London?

Joy: In New York. My friend Jenny, who’s a really good friend of mine, was going to New York and said, “I want you to come to New York because you’ve had the worst set of events happen. I think it would be good for you to have some time away.” I said, “Yeah, I agree,” and I came to New York. I was in Central Park cycling. It wasn’t a motorbike. I blacked out. Nobody knows what happened. I woke up the next day in intensive care at Mount Sinai Hospital. I woke up in the hospital, and they told me I had fallen off my bike and I had front lateral brain damage, perforated lungs, perforated liver.

Sharon: Oh my gosh!

Joy: I feel really grateful that I’m here.

Sharon: Yes. To back up a minute, what was the switch from marine biology? I understand you were dyslexic, but what made you decide you were going to be a jeweler or an artist? What was the catalyst there?

Joy: I don’t think there was ever a specific switch. I feel like art has always been a part of my life. It was always going to be that. I was always going to draw and make. I was also encouraged to do sculpture. I remember trying set design, because I thought that married my love of film and storytelling and theater with my ability to draw and sculpt. I thought, “Theater, that’s a realm that perhaps would work well.” Then I went and did a set design course. The fact that they destroyed all my tiny, little things, because they have to take them apart to take the measurements for how big certain props or things have to be, drove me mad. I couldn’t deal that I’d spend hours on these things to be taken apart.

I think it was probably the exhibition I went to see at The Glasgow School of Art. When I saw the show, I was really taken aback that all the pieces had been handmade. They were, to me, miniature sculpture. I hadn’t considered that jewelry could be this other type of art. Seeing these works, I thought, “Wow! This is really interesting, and I think there’s much more scope to explore within this medium.” I think that was the moment of change that made it for me.

Sharon: What is it about sculpture, whether it’s large or jewelry-size, that attracts you? Why that? Is it the feeling of working with your hands?

Joy: I think it’s a combination of things, partly because my father’s a sculptor. I remember watching him sculpt, and his ancestors were stonemasons. They were quarriers from the Isle of Purbeck dating back to the 12th century. I remember going to the quarries with my dad and thinking how amazing it was that this material was excavated from the earth. Then my father introduced me to sculpture. A lot of West African sculpture, Benin Bronzes, modern sculpture by Alexander Calder. Michelangelo and classical sculpture was all around me in Italy when we’d go and visit my grandparents.

I think sculpture has always been something I found interesting and also felt natural or felt like something I had a calling towards. My mom has always said I have this ability with three-dimensional objects. Even as a child, when I would draw, I would often draw in 3D. I do still draw a lot, but I often collage or sculpt to work out something. You often draw with jewelry designs, actual drawings in the traditional sense, but I go between all different mediums to find that perfect form I’m looking for.

Sharon: When you were attracted to this jewelry in Glasgow, did it jump out at you as miniature sculpture?

Joy: Yeah, definitely. Looking at it, I saw it as miniature versions of sculpture. I also find artists such as Rebecca Horn interesting in the way that they’re often about performance or extensions of the body. Even Leigh Bowery, who worked with Michael Clark, was creating physical artworks with ballet. These interactions with the body I think are really interesting: living sculpture, how those things pass over. I don’t really like categorizing different art forms. I think they can cross over in so many different ways. We have this obsession about categorizing different ways or disciplines. I understand why we do that, but I think it’s interesting where things start to cross over into different boundaries.

Sharon: That’s interesting. That’s what humans do: we categorize. We can spend days arguing over what’s art, what’s fine art, what’s art jewelry. Yes, there’s gray. There are no boundaries; there’s gray in between.

Tell us about your business. Is that something your folks talked to you about, like “Go be an artist, but make sure you can make a living at it”? Tell us about your business and how you make a living.

Joy: I felt my parents were going to support me in whatever decisions I made. My mom ran away from Italy when she was 17, and she always told me that she said when she was leaving, “You have to live your life, because no one else will live it for you.” She’s always had the attitude with me. Whatever direction I wanted to go in, I felt supported. I’ve always thought that if you work really hard at something or you put in the hours and you’re passionate about it, then things will grow from that. Every experience I’ve had has influenced the next thing. I never see something as a linear plan of exactly how I’m going to reach or achieve certain things. I’m still very much learning and at the beginning of it. I only graduated in 2019 from the Royal College of Art doing my master’s.

As I mentioned before, these two goldsmiths had given me an informal apprenticeship, basically. They were two working goldsmiths that had a studio, and they had been practicing for around 40 years. They had given me a space to work on this skill. Even though I studied a B.A. at The Glasgow School of Art, which is a mixture of practical and theoretical, I felt that after going to Japan and working with a samurai sword specialist making Damascus steel—it took him 25 years to get to the point where he was considered a master craftsman, this master in his craft. I felt like I had just started, even though my education in making had started from birth because my parents were artists and exposed me to all these things and encouraged me to make.

Within metalworking and jewelry work, there are so many techniques and so many things you need to take years to refine. Really, it’s been like 11 years of education: doing a B.A., then doing an informal apprenticeship, then doing my master’s. Only now do I feel like I’ve really found this confidence in my own voice within my work. Now I see the reaction from people, and I can help facilitate people on their journeys. I really enjoy that aspect of what I’m doing.

I’m still trying to figure out certain ways of running a business because it’s only me. My uncle runs a successful business in Italy in paper distribution, and he said to me, “Why don’t you expand or mass produce your work or have different ways of doing things?” This is where I find he doesn’t necessarily understand me as an artist. For me, it’s about process and handmaking everything. Perhaps that might not be the way I make the most money, but it’s the way in which I want to live my life and how I enjoy existing. My business at the moment is just me handmaking everything from start to finish. What’s really helped me recently is having support from the journalist Melanie Grant, who invited me to be part of an exhibition with Elisabetta Cipriani. It was with artists such as Frank Stella, Penone, who’s one of my favorites from the Arte Povera movement who also came northern Italy, from an area where my family is from.

Sharon: I’m sorry; I missed who that was. Who’s one of your favorites?

Joy: Penone. He’s the youngest of the Arte Povera movement in Italy that came out of Turin. He often looks at nature and man’s relationship to nature, the influence of it or connection. The piece of his that was on display was a necklace which was part of a tree that wraps around the décolletage. Then it has a section which is sort of like an elongated triangle, but it was the pattern of the skin from his palm. It’s very beautiful. His sculpture, his large pieces, are often trees forming into hands or sections of wood that have been carved to look like trees, but they’re carved. There’s also Wallace Chan, who is obviously in fine jewelry. Art jewelry is considered—I don’t know what to say—

Sharon: That’s somebody who has a different budget, a different wallet. Not that your stuff isn’t nice, but the gems in his things, wow.

Joy: There was Grima, Penone, Frank Stella. It was a combination of people who are considered more famously visual artists than fine jewelers. Then there was me, who was this completely new person in the art jewelry scene. I felt really honored that Melanie had asked me to put my work forward. I’ve always known what my work is to me. I see is as wearable artwork. But there was the aspect of, “What do other people see in it? How are they going to engage in this?” The feedback was absolutely incredible.

Since then, the work and the business have been doing so well. I have a bookkeeper now. The one person I employ is an amazing woman called Claire. She has been really helping me understand how my business is working and the numbers. However talented you are, if you don’t understand how your business is working, then you’re set up to fail. It’s really difficult to continue to stay true to my principles and how I want to make, and to try to understand how I’m going to be able to do that, what it’s going to take. I’m right at the beginning of it. I’m only in my first two years of my business. At the moment, from speaking to Claire, she was saying I’m doing well. I feel really supported by my gallery also, and that’s the big part of it. I think that’s going to make the difference.

Sharon: Wow! You do have a lot of support. No matter how talented you are, you do have to know how much things cost, whether you’re making by hand or mass-producing them. I’ve always wanted to stick my head in the sand with that, but yes, you do need to know that.

I didn’t realize there were so many artists at the exhibit. I knew you had this exhibit at Elisabetta Cipriani’s gallery, but I didn’t realize there were so many artists there. That must have been so exciting for you.

Joy: It was super exciting, and it was really interesting. Melanie has just written this book, “Coveted,” which is looking at whether fine jewelry can ever be considered as an art form. That’s a conversation I’m sure you’ve had many a time in these podcasts, about classification. It’s what we were talking about before, about how everything becomes departmentalized. Where is that crossover? How does it work? If people say to you, “I’m a jeweler” or “I’m an artist,” you’ll have a different idea immediately of what that means.

It was hard to present an exhibition which was a combination of different work with the interesting theme of “force of nature,” just as we were coming out of lockdown. These are artists who’ve all been working away, and we got to do a real, in-person exhibition that people could attend and see and touch. One of the most magnificent things with jewelry is the intimate relationship you have with it, being able to touch it, feel it, that sensory aspect. I think in this day and age, we have a huge emphasis on the visual. We’re bombarded with visual language, when the tactile and touching is the first thing we learn with. To be able to touch something is really to understand it.

Sharon: I’m not sure I 100% agree with that philosophy. I have jewelry buddies who say they have to hold the piece and feel it. I guess with everything available online, I don’t know.

Joy: Diversity depends on what your own way of experiencing things is. Also, the way you look at something will be informed by the way you touched it. Yes, we are all looking at things big picture. We know it’s made of wood or metal or ceramic. We can imagine what that sensation is. Of course, imagination also influences the ability to understand something, so they work together. I think it just adds different dimensions. It’s the same with music. Sound is another sensory way in which we experience things. Music often moves me and helps me relax in ways that other art forms don’t do.

Sharon: Right.