Episode 153

What you’ll learn in this episode:

- How Jonathan moved from sculpture to jewelry to drawing, and why he explores different ideas with each medium

- How the relationship between craft and fine art has evolved over the years

- Why people became more interested in jewelry during the pandemic

- Why jewelers working in any style benefit from strong technical skills

- How you can take advantage of the 92nd Street Y’s jewelry programming and virtual talks

About Jonathan Wahl

Jonathan Wahl joined 92nd Street Y in July 1999 as director of the jewelry and metalsmithing program in 92Y’s School of the Arts, the largest program of its kind in the nation. He is responsible for developing and overseeing the curriculum, which offers more than 60 classes weekly and 15 visiting artists annually. Jonathan is also responsible for hiring and supervising 25 faculty members, maintaining four state-of-the-art jewelry and metalsmithing studios, and promoting the department locally and nationally as a jewelry resource center.

Named one of the top 10 jewelers to watch by W Jewelry in 2006, Jonathan is an accomplished artist who, from 1994 to 1995, served as artist-in-residence at Hochschule Der Kunst in Berlin, Germany. He has shown his work in the exhibitions Day Job (The Drawing Center), Liquid Lines (Museum of Fine Arts Houston), The Jet Drawings (Sienna Gallery, Lenox MA, and SOFA New York), Formed to Function (John Michael Kohler Arts Center), Defining Craft (American Craft Museum), Markers in Contemporary Metal (Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art), Transfigurations: 9 Contemporary Metalsmiths (University of Akron and tour), and Contemporary Craft (New York State Museum).

Jonathan was awarded the Louis Comfort Tiffany Emerging Artist Fellowship from the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, two New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowships in recognition of “Outstanding Artwork,” and the Pennsylvania Society of Goldsmiths Award for “Outstanding Achievement.” As part of the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, TX, and The Museum of Arts and Design in New York, his work has been reviewed by Art in America (June, 2000), The New York Times (June 2005), and Metalsmith Magazine (1996, 1999, 2000 2002, 2005, 2009); his work was also featured in Metalsmith Magazine’s prestigious “Exhibition in Print” (1994 and 1999). Jonathan’s art work can be seen at Sienna Gallery in Lenox, Massachusetts, which specializes in contemporary American and European art work, and De Vera in Soho, New York. His work can also be seen in the publications The Jet Drawings (Sienna Press, 2008), and in three collections by Lark Books: 1,000 Rings, 500 Enameled Objects and 500 Metal Vessels.

Before joining 92Y, Jonathan was, first, director of the jewelry and metalsmithing department at the YMCA’s Craft Students League, and later assistant director of the League itself. Mr. Wahl holds a B.F.A. in jewelry and metalsmithing from Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and an M.F.A. in metalsmithing and fine arts from the State University of New York at New Paltz. He is a member of the Society of North America Goldsmiths.

Additional Resources:

- Website: www.jonathanwahl.com

- Website: www.92y.org/jewelry

- LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/jonathancwahl

- Instagram: @jonathancwahl/

Photos:

Jonathan Wahl, Life Liberty, 17x12x6, fabricated tin Museum of Fine Ars Boston

Jonathan Wahl, Life Liberty detail 17x12x6, fabricated tinware 1994 Museum of Fine Arts Boston

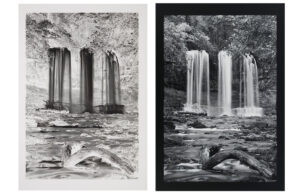

Black Waterfall 2, positive & negative comparison

Transcript:

With more than 60 jewelry classes offered weekly, the 92nd Street Y’s Jewelry Center is by far the largest program of its kind in the country—and it’s all run by award-winning sculptor, jeweler and artist Jonathan Wahl. He joined the Jewelry Journey Podcast to talk about the different relationships he has with jewelry and sculpture; why craftsmanship should be embraced by the art world; and what he has planned for 92Y in 2022. Read the episode transcript here.

Sharon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Jewelry Journey Podcast. Here at the Jewelry Journey, we’re about all things jewelry. With that in mind, I wanted to let you know about an upcoming jewelry conference, which is “Beyond Boundaries: Jewelry of the Americas.” It’s sponsored by the Association for the Study of Jewelry and Related Arts, or, as it’s otherwise known, ASJRA. The conference takes place virtually on Saturday and Sunday May 21 and May 22, which is around the corner. For details on the program and the speakers, go to www.jewelryconference.com. Non-members are welcome. I have to say that I attended this conference in person for several years, and it’s one of my favorite conferences. It’s a real treat to be able to sit in your pajamas or in comfies in your living room and listen to some extraordinary speakers. So, check it out. Register at www.jewelryconference.com. See you there.

This is a two-part Jewelry Journey podcast. Please make sure you subscribe so you can hear part two as soon as it comes out later this week. Today, my guest is Jonathan Wahl, Director of the Jewelry Center at the 92nd Street Y in New York City. The program is the largest of its kind in the country. In addition to his life in jewelry, Jonathan is an award-winning artist whose work is in the permanent collections of prestigious museums. It has been exhibited nationally and internationally. We’ll hear more about his jewelry journey today and how art fits into that. Jonathan, welcome to the program.

Jonathan: Thank you, Sharon. It’s a pleasure to be here. It’s a pleasure to see you.

Sharon: It’s nice to see you. Hopefully next time, it’ll be in person.

Jonathan: I would love that.

Sharon: Jonathan, tell us about your jewelry journey. How did you get to jewelry? Was that where you originally started out?

Jonathan: Recently I’ve been doing a lot of interviews myself with artists around the world—virtually since the pandemic—as Director of the Jewelry Center, and one of the questions I always ask them is “How did you find your way to jewelry?” It’s one of the questions I love to be asked because, at least for myself, it was interesting. I think all of us start out as artists, unless we’re born into a jewelry family. Everyone learns how to draw. Everyone paints on their own. Maybe they have classes in high school. If you’re lucky, you have a jewelry class in high school. I didn’t, so like many people, I discovered jewelry in college at Tyler School of Art, which has one of the best jewelry programs in the country, but I didn’t know jewelry existed until I went to art school.

When I went to art school, I thought I was going to be a graphic designer. Being the son of a banker and coming from a prep school, I figured I was going to be an artist, but I had to make a living. I wasn’t going to be a painter, so I was thinking I was going to be a graphic designer when I grew up. At the college, I discovered jewelry in my sophomore year. Stanley Lechtzin said to me—I’ll never forget it—“After you graduate you could design, if you wanted, costume jewelry in New York City,” and I thought, “That sounds kind of exotic and fun in New York City.” That’s how my jewelry journey really began, in an elective class as a sophomore at Tyler School of Art.

Sharon: Where is Tyler? I’m not familiar with it.

Jonathan: In Philadelphia. It’s part of Temple University.

Sharon: And Stanley Lechtzin, is he one of the professors there? I don’t know that name.

Jonathan: Stanley Lechtzin really put the program on the map. He’s in collections internationally. He pioneered the use of electroforming in individual objects. Electroforming was a commercial process used throughout the country for many different industrial applications, but Stanley figured out how to finetune it for the individual artist. His work has recently had some new-found appreciation because of the aesthetics from the 60s and 70s that are also coming back into vogue. His pieces are extraordinary.

Sharon: Before you came to the Y, did you design jewelry? Did you do art? Did you come home from your banking job and work on that stuff?

Jonathan: My father was a banker. I was not a banker. The closest I got to banking was working at a casino in Atlantic City one summer. My family has a house in Ocean City, New Jersey, so I could get to Atlantic City. I had to count a bank of anywhere between $30,000 and $70,000 a night. That’s the closest I got to being a banker.

I quickly then moved to London. This was the summer of my senior year after Tyler. After I graduated from Tyler, I moved to London briefly and worked for a crafts gallery in northern London. Then I decided I wanted to go to graduate school. I came back for about a year to work towards applying to graduate school, which ultimately became SUNY New Paltz. I graduated Tyler in 1990, so most of my undergraduate years were in the 80s. If you’re familiar with 80s jewelry, it was no holds barred. It was any kind of jewelry you wanted. My work—or at least my practice—quickly started to veer away from jewelry and towards objects and what I would call small sculpture. My choice to go SUNY New Paltz was specific because I didn’t really want to make jewelry, but I was interested in the field and decorative arts, the material culture of jewelry and metalsmithing. That’s what I pursued while I was in graduate school. I was recreating early American tinware about my experience as a gay American at that time. I wish there were visuals included, but that’s what I was doing at SUNY New Paltz.

Sharon: How did you find that material?

Jonathan: The tinware was a metaphor for America, for traditionalism. The pieces were metaphors for the function or dysfunction of America. These objects were a little perverse, a little sublime and really honest about how frustrated I felt about being an American and growing up in Philadelphia during the bicentennial. I thought life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness was for everybody, but I found myself not really able to access the full extent of that saying, like many people in our country even today. But I’m happy to report that a piece from that era was just acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I’m thrilled that the older work is getting some interest. There’s some interest from the New York Historical Society, which is not finalized yet, but it’s interesting to see that work with new eyes 20-some years later.

Sharon: Congratulations!

Jonathan: When I was in Germany, my partner at the time was finishing his master’s degree, and I was an artist in residence there at the Hochschule der Künste, which is now the Academy of Art, I think it’s called. That was an interesting experience because Europeans in general, and Germans in particular, approach craft differently. They have a much longer and supportive tradition of craft of all kinds, so when they saw my tinware, it was a little confusing to them. I ended up in a program called small sculpture as an artist in residence because there was no jewelry program at this art university. It was interesting. It was curious.

Sharon: Tell us how you came to jewelry.

Jonathan: Jewelry eventually gets into my story. After leaving Berlin, I moved to New York. I knew I wanted to be a New York artist. That’s the place I had to go. That’s the place I had to find my destiny. I was walking around looking for positions in a gallery, which was what I thought I was supposed to do. I walked into one gallery and the director there said, “I don’t have any gallery work for you, but I’m on the board of a not-for-profit gallery at the YWCA. That’s the home of the Craft Students League. They are looking for a program associate, which pays a ridiculously low hourly wage but has health benefits.” I thought, “O.K., I can do that.”

That’s when I found myself in the not-for-profit arts administration position that was developed into what I do now, at least part time. I was the program coordinator for the Craft Students League, which is unfortunately gone now, but had a wonderful ceramics, jewelry, painting, and book arts department. I ultimately became director of the jewelry studio and metalsmithing studio there, and then I became the assistant director of the whole program before I moved to the 92nd Street Y to become the director of the Jewelry Center here.

Sharon: Did they have an opening? How did you enter the 92nd Street Y?

Jonathan: Yes, there was an opening. There was John Cogswell. The Jewelry Center has some wonderful previous directors. It was Thomas Gentile from the late 60s to mid-70s, who really put this program on the map. He was followed by John Cogswell until the early 90s. Then briefly Shana Kroiz took over. She was between Baltimore and New York, and when she left the department, there was a call for a new director. That’s when I joined the program here.

Sharon: Wow! I didn’t know that Thomas Gentile was one of the—I don’t know if you want to call it the founders, but one of the names that launched it.

Jonathan: Yeah. The program began in 1930 in its earliest form as a class in metalworking and slowly evolved into a few more classes. It became part of the one of the largest WPA programs in the country here at the 92nd Street Y, but it kind of floated along until Thomas came—and Thomas, forgive me if I get this wrong—in the mid-60s, I think, maybe later. He came in and really started to formulate a program of study here. He was the one who really created the Jewelry Center as a center.

Sharon: Was he emphasizing art jewelry or all jewelry?

Jonathan: There was a great book put out by the Museum of Modern Art in the 50s about how to make modern jewelry. Now, I don’t know if the MOMA realized that they put out a book on how to make jewelry, but my point is in New York, I think there was still this idea of the modernist aesthetic and the artist as jeweler or jeweler as artist. I would say that Thomas was focused more on artist-made jewelry, the handmade, the one-of-a-kind object. It was still not looking in any way towards traditional or commercial jewelry.

Sharon: Jonathan, tell us what the 92nd Street Y is, because people may not know.

Jonathan: The 92nd Street Y is a 140-year-old institution here on the Upper East Side of New York City. It is one of New York City’s most important cultural anchors. It has many different facets. We have a renowned lecture series. The November before the pandemic, I remember we had back-to-back Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Lizzo. Wednesday night it was Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Thursday night it was Lizzo. Last night we had Outlander here, and I think we had a full house of 900 people plus 2,000 people online. We also have a world-renowned dance center that has a long history with Martha Graham and Bill T. Jones. In many ways, modern dance coalesced at the 92nd Street Y. The Jewelry Center has had a presence here at the Y since 1930. We have a wonderful ceramic center. We also have one of the most prestigious nursery schools in New York City. You name it.

The 92nd Street Y is a Jewish cultural center. It’s part of the UJA Association, but it’s kind of its own thing. It’s a whole other story about what Ys are and the difference between YWCAs, YMCAs and YM-WHAs, which is what we are, but the 92nd Street Y is really a cultural center.

Sharon: When are you opening your West Coast branch in Los Angeles? Because you have such an incredible number of speakers and programs.

Jonathan: Many of them come from the West Coast. We had Andrew Garfield here the week before last to talk about his amazing performance for a Reel Pieces program with Annette Insdorf. I think that was a full house of 900 people for a performance from “Tick Tick Boom,” which was great. I don’t know when we’re coming to LA. We’re just reemerging from the pandemic here in New York.

Sharon: This is not related to jewelry, but do you think that without the pandemic, you would have gone online to such an extent? Would it have been possible for people around the world, including on the West Coast, to see what’s going on?

Jonathan: The pandemic was the catalyst to do something we’d always thought about, but yes, the pandemic definitely forced us to do it. On March 13, New York City shut down. That Monday, we flipped all of our classes, every single one of our classes in the Art Center, which is about 200 classes, to be virtual. That worked for some classes better than others, obviously for painting and drawing. It was fine for jewelry. It’s tough if you don’t have a studio. What we did through the summer is offer online classes. We still offer online classes to some extent, but my focus is on building back our in-person class schedule, which we’re doing. We’re over about half enrollment now from the pandemic and moving quickly towards three-quarters.

Sharon: Did the people who enrolled in hands-on jewelry classes, did that just stop with the pandemic?

Jonathan: Yes, it stopped from March 2020 until September 2020. In September, we actually opened back up for in-person classes. We wore masks. We were socially distanced. We were unvaccinated. I was taking the subway and it worked. It was slow at first, but I think this process is a part of many people’s lives and this program is so meaningful for so many people. Being in New York, access to a studio is important, and very few people have studios at home. This is not only an important part emotionally of their lives, it’s also literally, physically, an important part of making jewelry their practice.

Sharon: Since you started as director of the program, I know you’ve been responsible for growing it tremendously. Was that one of your goals? Did you have that vision, or there was just so much opportunity? What happened?

Jonathan: All of the above. There was a lot of opportunity. Unfortunately, the Crafts Students League closed shortly after I left. Parsons closed their department. There were a number of continuing education programs that left Manhattan, and this is before the country of Brooklyn was discovered, even though I lived there. There were no schools in Brooklyn, really. The 92nd Street Y became one of the few places to study when I came on.

Also, to my point about studying jewelry in art school, you’re studying to be an artist generally in art school; you’re not really studying to be a jeweler in the way most people understand jewelers to be. Although certainly at Tyler, it was a great technical education and I learned a lot of hard skills, many people, including myself, were not adept at those hard skills. We’re not taught at a trade school, and I found that most of the people who were looking for jewelry classes wanted to make more traditional jewelry than the classes we were offering. Most of our faculty came from art school. There were some amazing people, Bob Ebendorf and Lisa Grounick(?) to name just a few, but as the 90s wore on and the aesthetic changed, I found that people really wanted to learn how to work in gold, how to set a stone. The aesthetics of jewelry shifted. You probably know yourself that the art jewelry world shifted a little bit too. For myself, I wanted to learn more hard skills, and I basically started creating classes that reflected my interests in how to make better wax carvings, how to set a brilliant-cut stone. I can then make that into what I want: studio jewelry, art jewelry, whatever, but those hard skills were lacking.

I’ve said this many times: I don’t know that this program would exist in another city other than New York because there was so much talent here. There were people from the industry here. There were artists who were studio jewelers and art jewelers all at my fingertips. I think that was one of the ways it grew, not because I reduced the perspective of what was being made here, but because I enlarged the perspective of what was being made here or taught here.

Sharon: How did you do that? Did you do that by identifying potential teachers and attracting them? What did you do?

Jonathan: I was lucky to have some wonderful people in New York City at that time. We had a wonderful faculty to begin with, but we also were able to expand the faculty with incredible people who had recently resigned. Pamela Farland, who was a master goldsmith and was the goldsmith at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for many years, was on our stuff. Klaus Burgel, who was trained at the Academy of Munich, was here in New York and came to us as a faculty member. Tovaback Winnick(?), who was a master wax carver and worked for Kieselstein-Cord for many years, came on as well. Some people work here for a shorter period of my time. My good friend, Lola Brooks, was here and taught stone setting. There was some really stellar talent around that helped me build this program.

Sharon: That’s quite a lineup you’re mentioning.

Jonathan: And a really diverse lineup.

Sharon: Diverse in what sense?

Jonathan: Klaus’ work is pure art jewelry: the iconic object, incredibly crafted, but what one would consider as art jewelry in its most essential sense. Lola Brooks, her work crosses the lines of both art and jewelry, and she’s got a beautiful studio jewelry line. Then there are people like Pamela Farland, who made very classical, Greco-Roman, high-carat granulated stones, classical goldsmithing. Then there was Tovaback Winnick who teaches carving, which is how the majority of commercial jewelry is made. We had real range as well as your regular Jewelry 1, Jewelry 2, Jewelry 3 classes where we’re teaching the basics of sawing, forming and soldering.

Sharon: You answered my question in part, but if somebody says, “I’m tired of working as a banker; I want to be a jeweler,” can you come to the Y and do that? Can you go through Jewelry 1, Jewelry 2, Jewelry 3 and then graduate into granulation? I don’t know if there’s a direct line.

Jonathan: Absolutely. We don’t have a course of study. We don’t have a certificate, but you can definitely come here and put your own skillset together. That’s also what I found strong about the program, that it gave people access to put their skillsets together without going through art school or going through college. You’re able to learn those hard skills in an environment where it’s no frills.

Sharon: Are they mostly younger people, older people, people of all ages?

Jonathan: It’s people of all ages. When I joked about the country of Brooklyn not being discovered yet, I lived in Williamsburg, Brooklyn for my whole New York life, so I’m speaking the truth. There really wasn’t anything out there. If you were young and hip and cool when I lived in Brooklyn, you had to come here. So, for a long time, we had a much younger population that was cool, hip. Now, everybody has moved to the country called Brooklyn. That demographic has aged a little bit for us.

We have three classes during the day. We have a morning class, an afternoon class, a late afternoon class and then an evening class. If you’re a younger person, it’s most likely that you have a job, so you’re going to come at night for our classes. That’s only one-quarter of the population that can take a class here, because there’s only one slot of night classes. There could be four classes happening at the same time, but all from 7:00-9:30. So, in general our population skews old because those are the people who are generally available during the day.

That being said, it’s New York City. There are lots of different ways to make a living here. There are definitely people who are actors or bartenders or artists or what have you who do have time during the day and come here. It really depends on what class, but absolutely; we have all ages for sure. We also have kids’ classes in the afternoon from 4:00-6:30.